In neoclassical DSGE models, coastal defences are ‘wasteful’. A reply to June Sekera

Dear mrs. Sekera,

thank you for your very clear and insightful blogpost on this blog about economists and their distorted concept of public goods. But I’m afraid you’re way too positive about mainstream macro models and ‘public goods’. Often – these models do not have a concept of public goods.

On a regular basis neoclassical ‘macro’ models do not have any logical space for public goods or ‘government consumption’ (i.e. consumption by households produced or financed by the government, like education). Which is, of course, daft. My country – the Netherlands – would not even exist without coastal defenses. And believe me – we learned about the necessity of well maintained large-scale public coastal defenses the New Orleans hard way (Knibbe, forthcoming). After every major flood there was a wave of public centralization and extension of planning, design, control and financing. ‘Wie niet dijken wil moet wijken’ (those unwilling to pay and build a coastal levee – must flee). We actually built a statue for Caspar de Robles, a Spanish oppressor who was kicked out during the Dutch Revolt, because he improved financing and building of levees in Friesland in the sixteenth century. But in the default neoclassical macro economic DSGE (Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium) models, public expenditure on coastal defenses is, by definition, ‘wasteful’ – as it’s government expenditure. And government expenditure, all of it, is wasteful in these models as it uses resources which could be used for private consumption. A nurse paid by the UK National Health Service is ‘wasted money’, a privately paid nurse adds to utility. That’s the state of mainstream macro-economics, neoclassical style. You are attacking Samuelson – but Samuelson crafted his ideas (which as you state do have basic flaws) to combat exactly this kind of thinking! He clearly failed. This kind of thinking is alive and kicking. And kicking hard – as the over five million unemployed in Spain can testify. Even incorporating the flawed ideas of Samuelson into these models would be a huge step forward. These at least consider the existence of public goods and services.

The Oosterscheldekering coastal defense. Wasteful?

There are endeavors to change this. But the very fact that these articles have to state, in an explicit way, their difference with ‘standard’ neoclassical ‘macro’ by introducing the notion that public expenditure can serve a purpose shows the ‘state of the mainstream art’: unmitigated market fundamentalism. Don’t misunderstand me. I do consider governments to be dangerous entities as, in Europe, the shift of power to undemocratic institutions like the ECB and the Troika shows. Also ‘the left’ should embrace all efforts to attain a world guided by less and simpler rules. A goal which might only be attainable by limiting the number of government bureaucrats. Despite this caveat I like ‘my’ coastal defences very much (financed and designed by the government, built by private companies). Also, the teachers of my children do an excellent job. Dutch roads are excellent. Such public goods and consumption are, however, neglected by DSGE-economist or, to phrase it in their language, ‘public consumption does not enter the utility function of the representative consumer’. Not even in a Samuelsonian way. Remarkably, the neglect of government products and services is not ordained by the logical structure of the models. It is a choice by the economists designing these models, as models which do admit the existence of government products and services show.

Two examples:

The first example is an article by Yasuhara Iwate (2012) aptly titled: Non-Wasteful Government Spending in an Estimated Open Economy DSGE Model:Two Fiscal Policy Puzzles Revisited.

The naive among us might read this title the wrong way, as it seems to implicate that DSGE models as a rule make a division between wasteful and non-wasteful government spending. But it doesn’t. The title is meant to indicate that the article departs from the general habit of these models of treating all government spending (coastal defenses, education, health) as wasteful: ‘very few papers have considered non-wasteful nature of government spending‘. It does this by introducing the notion of ‘Edgeworth complementarity‘, i.e. the ‘revolutionary’ idea that people privately owning cars benefit from the existence of (public) roads. This is necessary to solve two supposed puzzles: “Contrary to theoretical predictions, recent empirical evidence suggests a crowding-in of consumption and a depreciation of the real exchange rate after a government spending increase“. Wow. More and better roads and bridges leads to more traveling. To economists, this is a genuine puzzle. Households (the household…) in these models are ‘rational’ and ‘Ricardian’ in the sense of the economist, i.e. increasing wages of teachers is supposed to lower consumption this wage increase is wasteful… Which is wrong when we look at the behavior of real households. But the puzzle is solved when we consider the fact that government consumption might have a useful purpose, like high quality education.

The Millau bridge – public/private partnership. Wasteful?

The second example is a 2011 article by Stähler and Thomas with titled: “Fimod – a DSGE model for fiscal policy simulation“.

This article takes the ‘revolutionary’ approach that parents actually like it when their children get an education: public consumption directly enters the utility function of the representative consumer. There are actually two consumers in this model but they do not interact in a genuine social way as, contrary to real life, their interactions do not change their attitude, their sense of self or their balance sheets. Which means that ‘utility’, as used in this model, still adheres to the neoclassical concept. A fun part of the article is that is uses the concept of the rational Ricardian household which increases expenditure (as long as it can borrow) when the government cuts wages and dismisses people as the household perceives this as ‘less waste’ and hence more space for private consumption:

Because of lower private wages, less public employment and an increase in unemployment, consumption of RoT households [households which can’t borrow, M.K.] falls, while it increases for optimizing households due to anticipation of lower future taxation; the latter effect dominates, and thus total private consumption rises.

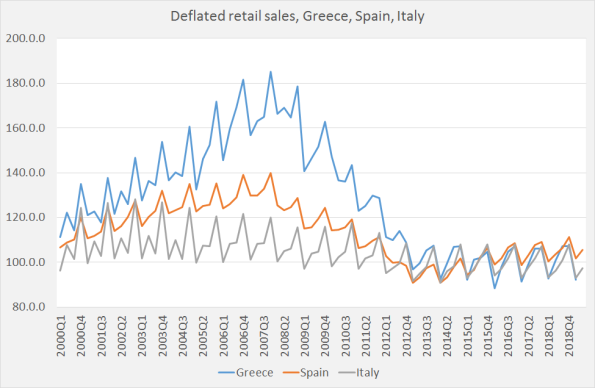

This is called expansionary austerity and it does not exist. Cutting government wages and sacking government employees did not exactly lead to a consumption surge in southern Europe.

But that’s all about private consumption, back to public consumption. What happens when we concede (as this model does) that government financed education is not wasteful by definition (i.e.: ‘enters the utility function’)? The model becomes kind of indeterminate in its results. The joyful austerity idea that a crisis is best solved by crushing the government vanishes into thin air, even when direct beneficial effects of government consumption are excluded:

However … in our model, we neglect any potentially positive (say, for instance, private productivity-enhancing) spillover from public employment to the private sector. Government services only enter households’ utility [i.e. not the ‘production function’, learning children to read and write has no productive use, M.K.]. As it is not clear how much public employment (positively) affects private sector production, we chose to abstract from this issue. Nevertheless, the positive effects of public sector employment cuts found here are certainly diminished in practice (or may even vanish when public employment reduction is misplaced) … we find a cut in public sector wages to be beneficial for private sector output and for both private sector and total employment. … Our simulations suggest that cutting public sector wages is, in the short and long-run, the most efficient consolidation strategy in terms of economic activity, i.e. production and employment … However, again, we must point to some caveats regarding this finding. Cutting public sector wages (too much) may imply that the public sector no longer finds (qualified enough) workers to do the relevant tasks, or that public sector workers would no longer provide the necessary effort (a possibility the literature on efficiency wages points to). In both cases, the provision of public services may be affected. Given that public services enter the households’ utility, such measures may not necessarily be welfare-enhancing even though they increase economic activity. Furthermore, our model neglects the possibility that government services indirectly foster private-sector productivity.

Dear mrs. Sekera – these articles are the exception. They concede a possible, ‘Samuelsonian’, positive role for ‘public goods’. But the ‘default setting’ of these models is the idea that public expenditure is wasteful, by ideological nature. That’s a lot worse than Samuelson whose ideas, despite all their shortcomings, were in crafted to combat that kind of nonsense! We have to continue this struggle (at this moment in the Euro Area by enhancing democratic control of central banks). Samuelson forged the wrong weapons but even his ideas are not embedded in mainstream macro models, anymore.

Again, the government is a dangerous entity. On the other side – the heroic work of Savitribai Phule (1831-1897), the first women’s educator of India, is far from completed. And we need governments to do this. To much talent is still wasted, to many women – and men – are not yet empowered by public education. Economic models should admit this.

Did you read my response to Mrs Sekera before you wrote this, Merijn? Of course it’s fun, fair and thought-provoking, but I don’t find it particularly constructive.

How to enable the autistic or brain-washed economists who create the daft models you complain about “see themselves as others see them”? Get their “would-be-scientific” minds off hypnotic economics and onto the sciences of minds and information (as against those of brute force and ignorance)! The starting point of Shannon’s seminal ‘The Mathematical Theory of Communication’ was to REJOICE in redundant information and to work out how to make use of it to keep right what would otherwise inevitably go wrong. The same clear logical principle should be being applied to redundant workers – as it was of old by agricultural workers, who did maintenance when winters made them otherwise redundant.

Almost can’t believe this. If what you write about these (commonly used?) DSGE “models” is true, the mainstream economic ‘science’ is even more ridiculous then I thought.

Incredible.

How can they even consider these “models” useful in any way? And these are used for policy advice?

For quite some time I’ve been wondering why DSGE models do not have an explicit section about ‘politics’ as I assumed that their concept of consumption included ‘government consumption’ – and some entity of course decides about the army or whatever. It was only quite recently that it dawned upon me that they circumvent this problem by assuming a society without an army, without (at least primary and secondary) education, roads etcetera.

The reason why they circumvent this might be the Arrow paradox. Wikipedia: “In social choice theory, Arrow’s impossibility theorem, the General Possibility Theorem, or Arrow’s paradox, states that, when voters have three or more distinct alternatives (options), no rank order voting system can convert the ranked preferences of individuals into a community-wide (complete and transitive) ranking”. Which means that DSGE models with a political sector can’t assume ‘transitive’ macro preference rankings, which wrecks the whole endeavour.

Thank you so much for this, Merijn. You put the issue of Arrow’s paradox so simply that I can immediately see the answer to it, which is time-sharing: the dominant alternative (e.g. steering) giving way to the other alternatives (like correcting for drift or avoiding icebergs) at times when they have become significant.

Social economic behavour is guided by markets but also by governments, family ties, churches, fraternities, NGO’s – etcetera. It’s very strange when economic macro models only look at markets.

merijnknibbe (and others) – Thanks for your comments. And for the references to other articles.

Another worthwhile read is the paper by Paul Studenski. Though written in 1939, what he says about “government as a producer” is still highly important. I’ve pasted an excerpt below.

Government as a Producer

Paul Studenski

Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Vol. 206, GovernmentExpansion in the Economic Sphere (Nov., 1939), pp. 23-34

IN EVERY type of political organization known in human history, from the most primitive to the most elaborate, government has had to furnish services satisfying important needs of the members of the society, help them to make a living, influence their productive processes and consumption habits, manage economic resources to these several ends, and generally function as the collective economic agent of the people. The productive character of government activity was recognized by political and economic philosophers from ancient times down to the earlier part of the modern era. The relative goodness or badness of different governments was tested by these writers in no small measure by the extent to which these governments appeared to succeed or fail in the development of their countries’ economic resources and productive arts, and in the furtherance of the well-being of their populations….

…THEORY OF NONPRODUCTIVITY

Towards the end of the eighteenth century, however, under the influence of the industrial revolution, a sudden revulsion took place in the political and economic thinking of the time. The entrepreneurial class, in its quest for freedom from restrictive governmental regulation, attacked the ability of government to attend to the economic affairs of its citizens. Political economists took the view that business enterprise was the sole productive agency in society and that government was a passive, nonproductive, wealth-destroying orgaization. Thus, Adam Smith expressed this thought in his Wealth of Nations in 1776 as follows:

The sovereign . . . with all the officers both of justice and war who serve under him, the whole army and navy, are unproductive laborers. They are the servants of the public, and are maintained by a part of the annual produce of the industry of other people. Their service , how honorable, how useful, or how necessary soever, produces nothing for which an equal quantity of service can afterwards be procured. … In the same class must be ranked some both of the gravest and most important, and some of the most frivolous professions: churchmen, lawyers, physicians, men of letters of all kinds; players, buffoons, musicians, opera-singers, opera-dancers, etc.’

Strange as it may seem, this peculiar doctrine of the nonproductivity of government activity has tended to persist to the present day, and forms a fundamental tenet of the so-called classical and neoclassical schools of economics still dominant in this and many other countries at the present time. The theory of the nonproductivity of government activity is founded on several basic errors, to wit: (1) a tendency to regard government as an organization independent and apart from the people and pursuing its own advantage; (2) a wrong identification of economic activity with individual endeavor to make a living, and a failure to recognize the importance of collective economic effort; and (3) an unduly narrow commercial view of production as the creation of utilities having an exchange value. The exponents of the nonproductivity theory of government activity fail to see that government in modern democratic society, with which we are particularly concerned, is an agency set up by the people for their own advantage and controlled by them with a view thereto, and is, in fact, in some of its aspects, the people themselves acting collectively. Quite erroneously they conceive of government as being operated for the sole advantage of scheming politicians. It is wrong to conceive of economic effort as being purely individual in character. Under all forms of organized society, economic activity has required some collective effort in addition to the individual one, and this is still true of the modern society. The notion that production for exchange is alone “productive” is preposterous. [Emphasis added]

Like most people, I had little idea of government until I worked in it for ten years. One reason I could think of, for why I was so ignorant and was never taught properly about government, was that academics have an inherent bias in favor of government which is normally their paymaster.

When people talk about nonproductive government, they do not mean governments do not produce public goods, which they clearly do. (Studenski is attacking a straw man.) What they mean is: what governments do and their processes are often wasteful and unproductive. This has been my personal experience. Government inefficiencies tend to endure because there is a lack of transparency, limited accountability and therefore ineffective discipline.

Theoretically and typically businesses are subject to market discipline, which punishes mistakes and inefficiencies through losses and insolvencies. This market discipline has recently been suspended for big businesses such as banks by governments through bail-outs and subsidies, effectively preventing the proper operation of capitalism.

Economic textbooks never mention corrupt governments with corrupt politicians and bureaucrats. Only some economists consider government inefficiency through public choice theory and Austrian economics. They are rarely mentioned even in so-called “heterodox economics”. We need a balanced and unbiased view of government.

It’s probably true that government processes are in general not very efficient. If a business in a true free, competitive market would do the exact same thing it would probably do it a lot more efficient. Who knows, maybe 10, 20 or 50% more efficient. Depends on many factors I think.

However, there is efficiency and there is effectiveness. Effectiveness in the sense of what exactly is being done. And in general, government is there to do things for the public good which are in general -not- done by private businesses. It’s not in their interest (making profit in the short term). But these public tasks are very important in the long run. Education, health, public infrastructure, etc. It’s the foundation on which the private sector builds.

Economically, private company X could make stuff Y in a very efficient way. That’s “good” for the economy, measured by GDP. However those Y stuff are throwaway goods with no lasting value for society. At the same time, a government agency could build a road or hospital in a very inefficient way (meaning, paying too much to subcontractors from the -private- sector to do the work) but that thing has a lot of value in the long run.

Thanks for telling us your background, Lyonwiss, it explains a lot. I worked for the UK government, but not as an economist in the administrative side and “short-term” efficiency: as a scientist concerned with reliability, which is the other dimension of “overall” efficiency. [The word ‘efficiency’, incidentally, is in economics being used as a metaphor drawn from its steam engine theorising].

That is another aspect of what Matthijs is saying. It is not a lot of good being highly efficient, but only half the time!

Your comment also highlights mainstream economics’ misrepresentation of ‘government’ as if it were the administration of services and even the Administration as the dumb spokesmen so despised by the mainstream economists in the Treasury who administrate THEM. Most of the government adminstrated sector comprises public servants, most of whom, insofar as this is allowed by economists and unless contracted out by the likes of Thatcher, are rewarded for loyalty, knowing what they are doing and doing a good job. Now, to take the manifest case of mending potholes, their jobs are put out to contract and shoddily patched, not by locals caring for their own facilities but by “foreigners” in search of a profit, here today and gone tomorrow.

The significant problem with Government, I suggest, is not overall inefficiency but a few socially incompetent individuals being allowed to run the show, that that is as true of the private sector as of the public one.

Many years ago now I drew attention to the parallel between Mrs Thatcher and Britain’s medieval king nicknamed “Ethelred the Unready”. When he couldn’t keep his population of mixed Celts, Socts, Angles, Saxons, Vikings and Normans in order, Ethelred invited in foreign mercenaries to help him, and wondered why they helped themselves to our island’s riches.

I wish you could enlighten us about those supremely efficient corporations in which you made your career.

My experience, as well as the experience of my relatives, colleagues, friends and acquaintances in firms small and big, national and multinational, recent or well-established, in sectors ranging from computers and telecoms to bio-pharmaceuticals and aircrafts, paint a picture of organizations with islands of efficiency surrounded by bland mediocrity and wasteful ways of working, often persistent incompetence (especially in management), and all too frequently for comfort outright fraud.

Interestingly, those firms that are successful — with high growth rates and booming profits — also exhibit a high degree of sumptuary outlays and wasteful operations.

Perhaps you should remove your blinkers about “state” vs “corporate” efficiency, and realize that we are really dealing with human organizations, with common characteristics, advantages and foibles largely independent from their avowed economic purpose.

Just came across this: governments fighting ebola. No markets there (well, maybe in fake vaccins) http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-06-26/ebola-outbreak-worst-ever-needs-drastic-steps-who-says.html

Public goods are in public use. Just imagine everyone having to build their own roads to move. Talk about efficiency!

Private books are read usually once. Library books hundreds of times. Efficiency?

Anyway, I hate this obsession some people have about ‘efficiency’. Productivity growth brings us constantly more spending power and if government would somehow instantly become ‘efficient’ all that could possibly do is to bring us purchasing power that we will get anyway in couple of years. Big deal!

We got enough *stuff* already, more than enough. We are overworked (50-60% of people want shorter working times in europe) we got so much purchasing power that we replace still working items with never models just because year model has changed and we don’t know what else to do with our money. Off to the trash they go still working last-year models!

Government

I have principally been interested in government as an instrument through which technological progress is fostered. That can only be of interest to capitalists if they can make lots of money out of it. But most research unless it is government supported will not take place, since most businessmen are very ignorant about science and technology and only see commercial possibilities when they are obvious. Somebody said: If necessity is the mother of invention, then the Pentagon is the father of technology. All the major developments of information technology come out of the Defense Department. Apple, Microsoft, etc. made no major contributions to science-driven technology. The German economist Sombart also noted that war is the principal cause for technological invention. What about the idea that America’s lead technologically was a result of the American people pumping billions of taxpayers’ money into research and development during the Cold War. If the Americans just left the funding of new technology up to profit maximizing firms, which seems the ideology today, then the US technological lead will disappear.

This is just silly. A DSGE model is constructed to study economic fluctuations, for which government consumption matters mostly through its effect on aggregate demand. Thus, other features are abstracted from (just like in heterodox models), but that doesn’t mean anyone would use a DSGE model to derive optimal size of government or plan coastal defences.

Still, if you think that there are other, more direct mechanisms through which government consumption affects the business cycle, those can be incorporated, like the two linked papers show. And if you really want to study public goods, there is this field of “public economics” (with its own textbooks, JEL code and everything) you may want to become familiar with.

Dear Ivan,

you’r wrong.

Household consumption also effects aggregate demand – but is also incorporated in the utility function of the households. And government consumption does also effect aggregate demand but does, unlike private consumption, not enter the utility function of households in the standard DSGE model. Not in a direct way and not in ‘Edgeworth complementarity’ way. Which – accepting the idea that neoclassical ‘social utility’ is a worthwhile concept, which of course it isn’t – is daft: it should enter the utility function in *both* ways.

Ask yourselve the question: why did the authors of the papers feel the need to change the utility function of the household to include positive effects of government consumption (aside from affecting demand) and why did this change their conclusions so dramatically!

We should of course not ‘assume’ any kind of social utility function (the hubris, the hubris…) – but that’s another question.

If utility is separable in private and government consumption, the latter won’t affect individual actions directly (e.g. saving or labor supply decisions by households), so ignoring it (in utility) makes no difference. To get an effect, you need nonseparability, where marginal utility of private consumption varies with government consumption. Whether it does is ultimately an empirical question.

But now I’m wondering what do you think about heterodox models (be they Godley/Lavoie stock-flow models, Steve Keen’s differential equations or Sraffian linear activity economies, or whatever else you prefer). Since they typically don’t model individual preferences and utility functions at all (and your last comment indicates you agree with that), they must be ignoring welfare effects of public goods just as well.

Dear Ivan,

the point is not if utility is seperable. It is seperated in the models. And the point is that utility caused by government consumption is ignored.

Which brings me to genuine macro models like those of Godle/Lavoie. In those models you can’t leave out things at will (like the financial sector in DSGE models) without running into inconsistencies. They are much less ad hoc and much more coherent and systematic than DSGe models.

Great post Merijn — so, of course, the “usual suspects” have to show up and try to reduce interesting substantive theoretical and methodological issues/questions into “technicalities,” and as always defending the absurdities of DSGE, REH and EMH with a lots of if … if… if …, then …

Utility is not a scientifically proven concept. All published economic models (not just DSGE, EMH) are reductionist fallacies. They are reductionist because they attempt to reduce a complex economy to simple rules so that the economy runs predictably (at least statistically) like a machine. They are fallacies because their predictions contradict the facts of observation.

They are also unscientific because their efforts do not lead to iterative improvements of their models. What simple but significant truths have we learned from all this “pretense of knowledge”? How much proof do we need that the government cannot drive the economy like a machine using economic models?

The economic malaise we suffer is partly the result of poeple in charge applying the rubbish they learnt at university. Even students know this and have been protesting.

My view of some of these issues is

1) While governments very often (or are always) innefficient (for all kinds of reasons such as beurocrats who basically try to avoid working—eg police in the donut store, or just the sheer magnitude of buerocracy such as filling out of forms, etc. or because they make ‘inside deals’ with corporate friends—the congressperson to coporate lobbyist revolving door) I dont think businesses cn be argued to be that much more efficient even if they operate with ‘market discipline’. From an ecological economics view, a large fraction of what businesses produce is ‘junk’ (endless varieties of potato chips which end up as externalities, or trash on the street and CO2 in the air , whose costs should be internalized). Also while the computer revolution seems to be a pretty good argument for business efficiency, one has to remember it was partly born in the pocket of the taxpayer, who funded government research used to create it. Its possible some of those profits should be ‘given back’ (rather than say parked offshore to avoid taxes, or listed as tax exempt costs of doing business—eg to create a sky trust, or some sort of universal income).

2) The idea that one should get rid of utility functions reminds me of Mirowski, who seems to argue that math models used in economics, due to things like SMD theorem and inability to find a cardinal ranking of preferences (a gold standard of value ). His view seems to be we should get off that false road, and instead develop things like ‘Markomata’ (which appears to be his particular brand of computer —like my own “Ishian Economics’ which I think should replace Mankiw or Samuelson as the standard text required to be bought by all students of economics, so the student debt industry can realize more efficient profits, and I can get an income and become philanthropist—such as by buying pencils for the youth in my town who each fall have drives to buy them I’d also donate 1 copy of Ishian Economics which I’ll give during an elaborate ceremony with wine and cheese, for the elite) and my personal deliver and police escort will take me to for my announcement.

I’m not sure that Mirowski realizes that implcit in computer models such ABM is mathematics—-and indeed these typically involve a ‘cost function’ which is basically analogous to utility.

(I remember a guy with a PhD I knew who worked at IBM on cellular automota models—-he didn’t even seem to realize there were many mathematical representations of CA in differential equations or discrete games.).

While possibility not exactly isomorpjhic (1 to 1 correspondance, just as French and English may not say exactly the same things) , in general any model can be translated into or deduced from some other model, such as macro to micro, or deterministic to probabilistic.

3) I think the reason this is not discussed is essentially due to the utility of keeping certain people employed by having them repeat myths, stereotypes, perpetrate ignorance etc. Mankiw can keep his job repeating the mantyra, and some heterodox types can keep theirs by repeating its inverse. Just like people like Daniel Dennet can keep his job by saying the mind is reducible to a computer, while others can get jobs saying all we need is compassion and empathy (eg ‘iops’ and Parecon economics author Michael Albert) , or ‘new athesists’ can make cash denying the need for god, while others can make it in Megachurches saying its neccesary for both morality and making cash, by teaching the prosperity bible.

Utility to me is from Bentham—its the benefits minus the costs. While acknowledging both the failures of utility theory as well as its successes would be the way to go (just as noting that both atheists and religious people can be both moral and immoral) , basically it is wise to ‘rationally expect’ that being selfish is the rational choice or addiction so people should go along just to get along—eg join the Nazi party if its popular. (See M Hauser’s evilicious—though I wouldnt buy it because I dont think he needs another dime and also mostly just seems to be repeating his own mantra along with public goods knowledge of what is common sense to line his pockets and put something on his CV which will later be featured in the Museum dedicated to his life. ).

(the godle/lavoie stuff i havent seen, but seems to be on track, though I am sure I have seen similar models )

Too many people think about education as a magic that can cure all economic illnesses. Specifically that unemployment can be cured more education. But if there is too little demand in the economy all you are going to do is educating people into unemployment. And it is known fact that more educated people are, less they have desire to start up their own business, so there could be even fever jobs.