Capitalism’s growth problem

from David Ruccio

Contemporary capitalism has a big problem. And no one seems to be able to refute it.

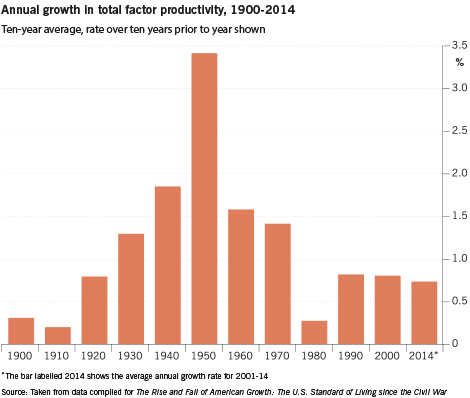

The problem, as Robert J. Gordon sees it, is that economic growth is slowing down, it has been for decades, and there’s no prospect for a resumption of fast economic growth in the foreseeable fure. After fifty (from 1920 to 1970) years of relatively fast growth, and a single decade (the 1950s) of spectacular growth, the prospects for continued growth seem to have dimmed after 1970.

In the century after the end of the Civil War, life in the United States changed beyond recognition. There was a revolution—an economic, rather than a political one—which freed people from an unremitting daily grind of manual labour and household drudgery and a life of darkness, isolation and early death. By the 1970s, many manual, outdoor jobs had been replaced by work in air-conditioned environments, housework was increasingly performed by machines, darkness was replaced by electric light, and isolation was replaced not only by travel, but also by colour television, which brought the world into the living room. Most importantly, a newborn infant could expect to live not to the age of 45, but to 72. This economic revolution was unique—and unrepeatable, because so many of its achievements could happen only once. . .

Since 1970, economic growth has been dazzling and disappointing. This apparent paradox is resolved when we recognise that recent advances have mostly occurred in a narrow sphere of activity having to do with entertainment, communications and the collection and processing of information. For the rest of what humans care about—food, clothing, shelter, transportation, health and working conditions both inside and outside the home—progress has slowed since 1970, both qualitatively and quantitatively.

From what I have read, Gordon appears to privilege technical innovation over other factors (such as dispossessing noncapitalist producers and creating a large class of wage-laborers, concentrating them in factories and cities, and so on). He also seems to argue that the fruits of past economic growth were evenly distributed and that the drudgery of work itself has been eliminated.

Still, the idea that rapid economic growth took place during a relatively short period of time dispels one of the central myths of capitalism, much as the discovery that relative equality in the distribution of wealth and constant factor shares characterized an exceptional phase of capitalism.

And that’s a problem: the presume and promise of capitalism are that it “delivers the goods.” It did, for a while, and now it seems it can’t—which has mainstream commentators worried.

They’re worried that capitalism can no longer guarantee fast economic growth. And they’re worried, try as they might, that they can’t refute Gordon’s analysis. Not Paul Krugman or Larry Summers or, for that matter, Tyler Cowen.

All three applaud Gordon’s historical analysis. And all three desperately want to argue he’s wrong looking forward. But they can’t.

The best they can come up with is the idea that the future is uncertain. Thus, as Cowen writes, “many past advances came as complete surprises.”

Although the advents of automobiles, spaceships, and robots were widely anticipated, few foretold the arrival of x-rays, radio, lasers, superconductors, nuclear energy, quantum mechanics, or transistors. No one knows what the transistor of the future will be, but we should be careful not to infer too much from our own limited imaginations.

Indeed. We certainly don’t know what lies ahead. But, since the 1970s, we’ve witnessed growing inequality in the distribution of income and wealth, which resulted in and in turn was exacerbated by the most severe economic crisis since the 1930s. Capitalism’s legitimacy, based on “just deserts” and economic stability, was already being called into question. Decades of slow economic growth and the real possibility that that trend might continue for the foreseeable future mean that capitalism (not to mention those who spend their time celebrating capitalism’s successes and failing to imagine alternatives) has an even bigger problem.

OK, that’s the second review of Gordon’s book that I’ve read, and I’ve heard Gordon interviewed, but none of them said anything about this guy: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kondratiev_wave

Is he in Gordon’s book?

I find it absurd to talk about capitalism’s legitimacy. It is not, after all, Israel. Capitalism exists as a force squeezed into shape by the regulatory framework it operates in, and hence it is a question of how that framework is changed to acquire greater legitimacy.

Limits to Growth? Back to the Future? How is a lack of “growth” a problem? We are a finite planet with finite resources with an economic system that assumes infinite growth and economists who promote it. The real issue is increasing complexity not all of which is captured in the GDP just as many other things are not captured in the GDP (e.g. so-called women’s work). If we view the economy through the lens of growth we miss the opportunity to actually view it realistically.

Even women’s work gets captured in GDP — this is the phantom GDP argument. The household conveniences have freed up women to do other things that benefit the family and community and in one way or the other, directly or indirectly, it gets captured in GDP.

You must approach capitalism as a process. That means you must consider it historically. The societies in which capitalism emerged first were no different than most other societies of the time. They were generally highly developed, with artisans and technicians of great accomplishment and had well run governments. By the standards of human history they were prosperous. But still they rested on the history of scarcity (particularly food scarcity) that existed since humans first formed villages and then cities. Two things changed this picture. First, the expansion of the energy available for useful work. First steam, then electricity, then the other fossil fuels were coupled with new machines (steam engine, electric lighting, electric manufacturing, etc.) to greatly reduce the fear and actuality of scarcity. Second, merchants invented double entry bookkeeping, LLCs, stock companies, etc. that not only increased the “money” wealth of most members of society but gave them new choices for spending that new wealth. Capitalism was off and running. Almost from that moment capitalism was criticized for its inequalities, its disturbance of traditional and customary ways of life, and its tendency to reduce everything in life to a bookkeeping entry. And there was revolution as well in efforts to fix these problems or simply eliminate capitalism. But capitalism continued and continues. As people became to expect the kind of society (wealth, goods to purchase, entertainment, etc.) it offered capitalism became embedded in everyday ways of life. But it remained fragile and easy to attack. So any errors on the part of supporters of capitalism were a great danger to its continuation. So as we might expect with human hubris these supporters got arrogant. And eventually that caught up with the system. Finally, it seems “financial” capitalism is on the brink of doing something that Marx and the USSR could never do — destroy capitalism. With a great deal of help from China. But also capitalism’s inherent problems grew to such a level and its own accomplishments lead to ever greater expectations such that the process is becoming no longer sustainable. In short, we need a new system. Capitalism’s day is over. What will replace it is the question on everyone’s lips now?

Hooray, someone noticed economies haven’t done as well in the neoliberal era as they did in the post-war democratic socialist era. Except the above discussions don’t frame it that way.

Lesson 1: laissez-faire doesn’t work, what works is to distribute the wealth more fairly.

Lesson 2: “capitalism” is not one thing, it is malleable, as MRK notes above. I don’t even know what people mean by the term. (Apart from “not communism”.)

Lesson 3: It’s more sensible to talk about how to run a market economy that delivers what we want or need.

Lesson 4: At present that is not “more, more, more”, it is “sufficient for a good quality of life and a thriving planet”.

https://betternature.wordpress.com/my-books/nature-of-the-beast/

Geoff, a few questions.

First, you say, “economies haven’t done as well in the neoliberal era as they did in the post-war democratic socialist era.” For you what constitutes “not working as well?”

Second, you say “laissez-faire doesn’t work.” What for you constitutes “not working?”

Third, I agree that operating a market that delivers what we want and/or need is the goal. But what is it we need/want?

Fourth, getting to “a good quality of life and a thriving planet” is a complicated process. You make it sound so simple.

Hi Ken,

1. By the mainstream’s own criteria of GDP growth, unemployment, inflation. By more holistic criteria it’s even worse.

2. Gross inequality leading to crashing markets, exacerbating other problems.

3. It’s called democracy – preferably without the propaganda of ms media.

4. Well we’re not even trying so far. So if we were trying we’d have a bit more chance of getting there.

Real GDP has jumped around since WW2 but you are correct sort of. Between 1950 and 1970 real GDP doubled. It doubled again by 1990. By 2015 real GDP had not yet doubled from 1990. The real news is that the US real GDP didn’t change much between 1930 and 1950. The post WW2 growth certainly surpasses anything that could have been expected based on 1930 GDP. You’re correct about the GINI index for the US. Its increase after 1980 is massive. I don’t understand how markets can be expected to produce democracy. Markets are not democratic in any way. How can they be expected to even support democracy already existing, let alone support creation of new democracies? Improving quality of life and a thriving planet requires first that there be a general recognition that the current quality of these can be improved and ought to be improved. From that can come the felt need to improve both.

We study history, as one branch of knowledge, to understand our place in the universe. The human animal is the one animal that has a cultural evolution as well as a biological evolution. We can shape and change that cultural evolution. We are the one animal that can change its environment and move about anywhere on Earth and beyond. The study of history is the link between the Past, the Present, and the Future – the link between knowledge and progress. Our progress as a species is linked to our quest for knowledge; and, technological advance and an understanding of our past is the key to the pace of that quest.

Technological progress does not slow down. It speeds up as you go through the ages. Listen to President Kennedy on YouTube on why we are going to the Moon and he gives an example of technological progress boiled down to 50 years, and the rate of development is ever faster.

Why does the 1960s compare so favorably to the last twenty-five years? Well look at the factors that really drive an economy and are the major determinants for economic growth: (1) an economy make-up where the different sectors of the economy feed off of each other, as they did in the 1960s, rather than perform independently of each other, like they do today; (2) where the productive resources are home-based, like the 1960s, rather than off-shored, like today, so that fiscal, monetary, and tax policies can work together for a better society – there is little fiscal stimulus to our productive resources today, most federal spending goes to ‘consumptive needs’ rather than to ‘productive resources’; and, (3) leadership in government and the private sector among business leaders and working people along with civic engagement in our participatory democratic society that places a greater value on the well-being of the broader society than personal gain; and if that sounds too altruistic for the1960s, it simply means that all who worked shared in the productivity gains of the enterprise rather than the situation you have had the past several decades were the few at the top take a greater share than the many below.

If you go through the 20th Century you see that people are becoming more educated; going from less than high school, to high school, to college and two-year technical degrees, and now to post-graduate studies. I do not know what the future holds, but I do not think the machines will take over. I believe people will have to devote a greater amount of their life to education for multi-disciplinary studies with a good technical background. Look around in the world, especially at all the under-privileged – there is plenty of potential to share our way of life with and improve the human condition. Economics is the study of allocating scarce resources. We have a way of life that is resource intense; so, there is plenty of potential for improvement, especially if we want to share our experience and values with others.

Phantom GDP – sorry I do not buy the argument.

The efficiencies derived from electricity and the internal combustion engine are all priced into GDP measures. They did not disappear anywhere. The savings from these efficiencies were reinvested into other productive resources and get depicted in a continuous stream of productivity increases and measured in GDP statistics. If you do not see the same thing going on today, especially with the impact of information technology, it is because it is not there; or, let’s say that the impact and improvement in productivity is not as great, small by comparison.

If there are efficiencies something must be done with the savings. The only way the savings would not show up in GDP is if you buried it out in your backyard or stuffed it under your mattress. I suspect we have paltry GDP numbers today (and for the past 15 years) is because the “savings” is going mainly into consumptive activities more so than productive activities that have a broad base of support in an $18 trillion economy.

The sectors that make up our economy are disjointed today in comparison to the 1960s. You only have to look at the California economy during 2010 after the Financial Crisis of 2008 and compare it to Texas. The Texas economy was humming because the Energy Sector was driving all the other sectors in the Texas economy; and, when oil prices dropped it affected the rest of the economy of the state. In California the only geographic area that was doing well in 2010 was the Silicon Valley – the rest of the state was still feeling the effects of the recession. If you want good economic growth in an $18 trillion economy you need all sectors working together and a broad-based sharing of the productivity gains by all who work, not the 1% (or the 10%) stiffening off the gains.

It has nothing to do with how you measure GDP — productivity is either there or it isn’t. Quality improvements should enhance efficiencies. If we are healthier, we live longer, we are consumers longer, we can do productive work longer if we want to – these all show up in GDP one way or the other. We are more of a service sector economy than a manufacturing/commercial that is because we have created an economy where we have a lot of low-wage, low-skill service jobs. The economy we have didn’t fall from the heavens. We created it. We can change it. There is much opportunity to do better if we want to take up the challenge.

I disagree with that chart you have from Larry Summers — did he factor out inflation?

Total Factor Productivity — 1950s to present (Interactive chart)

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=3nWZ

Here are the numbers off of the chart:

The annual rates of growth in GDP contributed by Technological Innovation alone (with inflation factored out, and the contributions of labor and capital factored out):

Total Factor Productivity:

1950s – 1.03%

1960s – 1.17%

1970s – 0.38%

1980s – 1.03%

1990s – 1.31%

2000s – 0.29%

2010s (through 2011) – 1.08%

So even when you factor in the impact of desk-top computers, the internet and the web, and the whole information technology boom period of the mid-1980s through to the present – you still do not reach the productivity of the 1960s in comparison to the best years of the 1990s from the charts above showing productivity growth of 35% for the 1960s and 25% for the 1980s and a little over 20% for the 1990s. In other words, the 1960s are 40% more productive than the 1980s and 70% more productive than the 1990s even though the 1990s had greater technology input.

David Ruccio’s graph is in two ways misleading. First, the rise in productivity to 1940 was due to rearmament and the spike in the 1950’s to making good the damage we’d done. Second, the graph is of American financial growth. It doesn’t account for the vast increase in, say, Chinese productivity and the overall massive use of real resources in exchange for minimal financial ones.

I was disappointed to see Ken Zimmerman questioning Geoff Davies’ summary judgements in quite the way he did. What one can see if one looks, cannot always be easily put into words, though Geoff’s “lessons” did try to reframe the previous arguments to tell us where to look for the reasons for his judgement. Pointing to what I see in answer to Ken’s questions

1. “Not working as well?” I’m with G K Chesterton in applying “the old utilitarian test of happiness (clumsy of course, and easily misstated) … The real difference between the test of happiness and the test of will is simply that the test of happiness is a test and the other isn’t. [It is a tautology]”. I remember people glad to and with the lasting satisfaction of having been able to help each other out during the war, then grateful for small mercies after it; but also the resentment caused by the re-emergence of market forces, when sweets (candy?) came off rations and the sweet shops were emptied within days by those who could afford to.

2. Laissez-faire “Not working?” The Catholic community in Britain still remembers the potato famine in Ireland, where millions died or fled as refugees to America because the British government didn’t insist that landlords growing other foods should share rather than export them. Rather as the United Nations now should be demanding Putin help rather than bomb the already suffering people of Syria. If laissez-faire works in the sense of allowing greedy individuals to temporarily make more money, it neverthess doesn’t work in the correlative sense of causing utterly unnecessary suffering.

3. “What is it we need/want?” What we don’t need is what we have already got, and what we do need is to maintain and care for it. What we do want is variety, and we need to make that compatible with both development and maintenance (as in re-engining or respraying cars). What we don’t want is the waste of a “throw-away” society.

4. (A disparaging remark about Geoff’s answer to 3, not a question): “You make it sound so simple.” At the start of the Hitler war, Dorothy L Sayers wrote a book called “Begin Here”, in which she challenged non-participant oldies like herself to agree on what they really want and work to make it possible, because if they didn’t, others would get what they want more. That helped inspire a conference in Malvern, which led to Anglican support permitting our post-war social democracy.

G K Chesterton reference surprises me on this blog. But okay. You do realize right that Chesterton was a traditionalist? Being selfish is not the same as Laissez-faire, but I get your point. Curing selfishness is gonna take a lot more than a strong government. Having more and more has become a cultural expected. To change that the culture will need to be changed. That’s a tall order. And one that most conservatives would say should not be attempted, and is impossible if it were. Making democracy is hard work. So hard that most people don’t want to be involved with it. They want freedom, or more accurately liberty. But they don’t want to do what’s necessary to make democracy. Democracy is duty and obligation to achieve and protect a way of life that allows freedom. Hard, hard work.

Ken, I agree culture needs to be changed, and that’s not easy. I also agree democracy is duty and obligation as well as “freedom”, and hard work.

I would just observe that modern so-called “conservatives”, meaning neoliberals, or neoconservatives in the US, are not conservative at all, they are radicals. They set about changing our culture to a self-centred, selfish one, and they’ve had some success. So culture can be changed, and we need to change it back, soon.

Geoff, observations accepted. And I agree many but not all current conservatives are indeed ideologists and sometimes even radical ideologists. Edmund Burke would not find either their views or their actions conservative. As one “conservative” put it when I asked what his goals were — “To make the country over so that me and my friends feel comfortable in it.” Old boys’ club made universal and permanent, I think he meant.

Ken and Geoff, The idea that individual freedom must be accompanied by a sense of social responsibility does not go very far in the English speaking world these days. I ran across it when reading about the German Idea of freedom. My point is that you must learn about more than the intellectual traditions of Anglosaxonia. It isn’t easy to do for people in management and economic studies, but there are lots of people in US and British universities who are familiar with the nonwestern world. Why are we not calling on them and economists in the nonwestern world, particularly Asia, for input. Otherwise you’ll just keep spinning your wheels in the muck of neoliberalism.

Robert, I’ve asked those same questions myself, often. Americans and British seem to have some sort of problem in comparing their ways with those of any other parts of the world. And they are both paranoid about actually using suggestions from any of these other places. The German idea of freedom is difficult to explain without using German. Suffice it to say that it’s less libertarian than the American freedom and less “stuck in time” than the British version. I work with American regulators. I’ve often tried to make the case they could learn a lot from Asian regulators. Even Chinese regulators have some interesting approaches. Mostly I get ignored.

And we don’t have to go very far to find alternatives. Tore Høie has been writing about the Nordic view of management in contrast to the American for years.

Thanks to Prof. Locke for referring to me. In 2015 two Danish companies were awarded World’s Best status. Novo Nordic’s boss was called World’s best boss by Harvard Business Review, Novozymes was found the best place to work for researchers by Science magazine. For 2015 Novo had 43% profit growth, they teach all employees ethics. You can be ethical AND earn money, perhaps in the long run ethics is good for earnings? For more, please read my book Ethics – The Future of Management, it can be ordered from tore.hoie@vikenfiber.no. We also need researchers who can investigate the role of ethics in management, much more needs to be done.

This is from Norway, our Oil Fund recently dumped 73 companies with low social responsibility. Perhaps a sign of the new world view?

Robert, my take on Anglo-Saxon attitudes is they had the experience of an expanding frontier. Americans in particular seem stuck on the Wild West mythology, and their libertarians seem to imagine you can be as independent as you wish and it won’t impinge on anyone else. That may have been true, briefly, on the frontier, but it’s not true in any actual society. Australia has its version, and it all seemed to feed back to Britain, which for a while expanded all over the world.

A good antidote to this nonsense is Greene, J., Moral Tribes: Emotion, Reason, and the Gap Between Us and Them. 2013: The Penguin Press HC. 432 pp. He argues we are intrinsically social with our “own” group, but indifferent and potentially hostile to people in other groups regarded as strangers. There must be a vast literature on the fact that we are highly social beings, and Greene’s is a good current summary, far from unique.

It means we surrender some of our autonomy for the benefits of belonging to a group. Fairly important when we were living on the African Savannah. There is no such thing as absolute freedom, except for hermits and perhaps, briefly, that Martian in the recent movie.

A point of biology still not widely appreciated is that cooperation is pervasive in the living world – as a strategy in the struggle for survival. The competition is much less “red in tooth and claw” than the old perception. So the neoclassical/libertarian neglect of cooperation is as misguided and dysfunctional as the communist neglect of competition.

The Taoists got it right a long time ago. A healthy life balances Yang and Yin, competition and cooperation. Trying to live at one polarity or the other is very unhealthy. The twentieth century demonstrated that rather clearly.

https://betternature.wordpress.com/my-books/sack-the-economists/

or, at a little greater length

https://betternature.wordpress.com/my-books/nature-of-the-beast/

Geoff, I lost my reply – essentially saying what you conclude here and in your previous comment – to Ken’s asking “Do I realise G K Chesterton was a traditionalist?” Well yes – having been given GKC’s “Orthodoxy” in 1963 and having since acquired a complete set of his books and lots appreciative as well as dismissive of him – though it took me all of twenty years to really understand his “Orthodoxy” and where it came from. (His earlier interests, as an art-schooled writer, in Left-Right personality differences, visual art and verbal language). But did Ken realise what sort of “traditionalist” was this “Seer of Science” (Jaki), whose “Orthodoxy” was “without any doubt the greatest work of English literature in the twentieth century” (Milward, 1981); who inspired Gandhi and E F Schumacher?

In “Orthodoxy” GKC says, “it is obvious that tradition is only democracy extended through time. … Democracy tells us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our groom; tradition asks us not to neglect a good man’s opinion, even if he is our father”.

But in 1908 he was not referring to the tradition created by the capitalists who had stolen rural property and forced the dispossessed – men, women and children – to live and work as wage-slaves in disgraceful industrial conditions, claiming “you can’t put the clock back”. That was current then, as is now happening again, globally. He was referring to the cooperative Catholic tradition which had evolved the previous rural way of life, in which conquering kings were held responsible to God and even feudal serfs had their own homes, arable strips and common woodland and pasture. This is where your “Yin and Yang” come in, Geoff. Superficially, GKC’s equivalent were what we call Church and State, but his whole writing style was about conjuring up vivid pictures in a few words, humour from ambiguity, serious thought from paradox. Even the word “Orthodoxy” is a pun. Does it mean “right teaching” in the sense of (self-adjudicated) correct, or in the sense of orthogonal: with complementary dimensions visually at right angles?

I am going on about this, Geoff, because you refer to Yin and Yang as polar opposites, which are NOT complementary, but tend to cancel. A lot of misunderstanding and ill-will can be avoided simply by changing the conventional teaching image from the rope of a Marxist Orthodox/Heterodox Right/Left tug of war to hanging complements on the cross of Cartesian coordinates, including the four parts of our brains and – as Chesterton put it in “Orthodoxy” – the insanity of using only [the linguistic] half of it. [Hence the value of GKC’s “The Outline of Sanity” in economics: imagining future possibilities not in the language of numerical graphs but by humorously conjuring up the evolved traditions of a suppressed and long-forgotten past. Admittedly, he didn’t seem to have a clue about how money is created; but then none of us is perfect].

Dave, you made me worry. Did I say “opposite” when I meant “complement”? Well I didn’t say either, I said “polarity” without being more specific. So to reassure you, I’m well aware that Yin and Yang are regarded as complements, not as opposites, and that’s certainly how I meant them.

Yes indeed, the West’s mistake has been insisting you have to choose between, rather than balance, competition and cooperation. A healthy life has plenty of both, and a healthy economy has plenty of both.

davetaylor1, thanks for the Chesterton information. I attended Jesuit high school and then a Marianist university for graduate school. So I know Chesterton well. In response to your comments, I can say that the economy today would look a lot different if the pre-capitalist Catholic ways of life had not been destroyed or subverted by capitalism. So in that Chesterton was making important points. The purest remaining area of such beliefs is found today, I believe in the social democrats of Bavaria (mostly Catholic). But we shouldn’t forget that many of these believers supported Hitler and Nazism in WW2. So Catholic-based economics is not an absolute protection for all forms of extremism. As for Chesterton’s support for the notion that science flourished in the west because of Christianity, I point out that science as it exists in the western world today existed previously in China and in the early Islamic Empire (European “Dark Ages”). A bit too much of a traditionalist for my tastes.

When one considers the development of co-determination in Germany, the Catholics, under Adenauer’s leadership in the CDU were certainly aboard, but so were the Protestants. Merkel speaks of it regularly, too. Within Protestant Europe’s Northern Countries, as Tore shows in his work on ethics, social responsibility thrived as well. The problems for Protestantism and Catholicism if to a lesser extent lies in their mainstream failures to challenge neoliberalism in the USA.

So you really believe the USA is as ISIS puts it, “The Great Satan?” The USA is just the empire that took over from the British. Fought the USSR to a standstill and then defeated it in a “cold war.” Spent more money on military weapons than any nation in the history of the world. And built the world’s largest economy (by GDP). That’s on one side of the equation. On the other we have Richard Hofstadter commenting that the success of the USA is no great achievement, considering the nation’s geography, resources, and location on the globe. USA the last major nation in the world to end slavery. Only Australia rivals the USA in the mistreatment of its native inhabitants. And the no nation has stolen more in its history than the USA. The USA claimed victory in WWII but really it was the USSR that defeated the Nazis, thereby ending the war in Europe. Actually even given all this, responsibility and duty to build community and help one’s fellows (economically and otherwise) remained strong in the USA (if sometimes grossly misdirected) till after the Civil War (remember 750,000 died in the Civil War and over 1,000,000 in WWII, for duty and obligation to social goals). And was rekindled after WWII. But the other side of that equation is that many immigrants came to the USA to be left alone and allowed to make as much money as possible. So business and making money have almost from the start been of equal importance to community in the USA. Since about 1970 the pendulum has swung strongly toward business and making money, and toward the USA as the empire that rules over the world. The consequences of this swing include the large economic inequity we see today and the massive USA military spending (larger than the military budgets of China, Russia, France, UK, Germany, Japan, Saudi Arabia, India, and South Korea combined). This can be reversed. It’s been reversed before. But doing it today will be particularly difficult because 70% of the USA population (or more) is ignorant of their own national history. Sort of like the blind leading the blind in a blacked out warehouse with snipers in every window.

Ken, who decides how the wealth in America is distributed today? In a regime of director primacy, it is the CEO and the board he/she appoints that makes those decisions. How, from a moral perspective, is this special elite educated . Traditionally, people thought that the leadership elite, because of the power they wielded, needed to be educated in the classics as Christian gentlemen because the moral education of the elite was more important to the achievement of a just society than its technical capability. So we have given directors primacy in deciding how the wealth will be distributed, without providing them in our current educational system in the US with a moral compass to temper their greed. That’s the fault of the post1970 generation that gave us neoclassical economics and the MBA.

I understand where you’re coming from, I think. But if the study of history is a teacher, as it can be, these “educated in the classics as Christian gentlemen” leaders could be and at times were quite brutal and uncaring. Depending on who or what was the focus of their attention. I cite the cases of the treatment of prisoners of war in the Franco-Prussian and American independence wars as just two examples. To carry the example in the direction you’re going, the treatment of prisoners of war has grown more brutal and uncaring since the times of these two wars. But I agree that many of the USA leaders do not have and have not been given the proper experiences to develop a moral compass to temper their greed (desire to accumulate).

As historians we both remember, the attempt right after World War II, to found an industrial democracy in America. Between 1948 and 1953 the Inter-University Labor Relations Program sponsored the publication of a significant academic literature (written by people like Clark Kerr, Fred Harbison, John Dunlop, Charles Meyer and others) emphasizing the extension of industrial democracy through collective bargaining with trade unions. This was an era when the gap between rich and poor was actually narrowing. But in the 1980s, under neoliberalism, management declared war on industrial democracy, sloughing off pension plans, medical plans, etc. Then the gap, especially with the financialization of the economy, between rich and poor began to grow. When the postwar era of US manufacturing dominance came to an end in the 1980s US management had a choice; form a partnership with your workers or turn your back on employees in the interest of what was called shareholder value and screw them. I saw it happen, to my dismay, the abandonment of industrial democracy by management. It did not have to happen, we had choices, and made bad ones.

Yes, I am aware of this history. And how it happened and the participants involved. But this sequence should not come as a complete surprise. The elements that make up what you call neoliberalism have been part of the make-up of the USA from its beginning, and even before. Now they have won the day and established themselves as dominant. As they were from 1880 to 1930 and from 1790 to 1820. But like all ideologies they failed, mostly because they failed in solving important problems and gathered too many enemies. No reason to assume this particular version of neoliberalism will do any better this time around. In fact, I’d say the end of its dominance is only a few years away; 2020 or 2025.

Geoff and Ken, thanks for your replies. As I said, Geoff, I ended up agreeing with you: obviously meaning “complements” though you said “polar opposites”. But can you hang scientific complex numbers, directed motion and an understanding of personality differences on Yin and Yang symbols more suggestive of the physical bodies of men and women?

Ken, Chesterton’s point (and indeed Bob Locke’s) was to see not just today’s dictionary translation of words like “tradition” and “extremism”, but to imaginatively see what they meant in their historical context. Agreed, Catholic-based economics was not an absolute protection against the likes of Hitler and Nazism (or Henry VIII and Capitalism), but this because Catholics are still just people at different stages of intellectual maturity, around 50% of whom still judge by their feelings, while the four areas marked out by the Cartesian cross divide personality types in the proportions 24%,52%, 20% and 4%, leaving only about 1% intuitives who think visually but are not satisfied with knowing and want to do something about it. As, like Chesterton, one of these myself, I‘ve virtually dropped out of Chestertonian circles because they has been taken over by literal minded enthusiasts (c.f. Evangelicals). He’s still a minority taste because of personality clashes one can see on the Cartesian cross.

As for GKC’s defence of Christianity against positivist scientists, I’ve nothing at all against Chinese toys, fireworks and medicine, the Greek Pythagoras’s Theorem and what I call Carpenter’s Truth (doorways standing upright), nor the Arabic invention of numerical algorithms; but the key word is “flourishing”. Francis Bacon transformed deductive science into taking things to bits to see how they work “for the glory of God and the relief of Man’s estate”; Galileo and Descartes were both Catholics who escaped judgement by the literal-minded; the brilliant Newton (though exhibiting Asperger’s syndrome) was still a Christian, unlike his atheist misinterpreter Hume. regarding yesterday’s magnificent achievement of the detection of radio waves, we’ve known the science of that for a couple of thousand years in the form of the twin black holes being the invisible energy (Spirit) of the Father and Son’s love for each other. As poets have put it, the Father so loved [the idea of] us he allowed his only begotten Son to die, that we might live. For that, should we not be truly grateful, and remember [in this time of economic and political distress] the Father now has no hands but ours?

Oops! What was I saying with my wife dragging me off out? Of course I meant yesterday’s detection of gravitational waves, not radio waves! Apologies.

Historical context is changed by history. In other words context is created by history and changes as history changes. So you can’t reach back to a context in the past, since that context is created by that history. Bringing it into another history changes it. No way to escape this I know of.

Your people at different stages of intellectual maturity is not workable. It assumes intellectual maturity is an inherent quality of the world, specifically of humans in the world. Rather than an historical invention created in a particular time and location. And that goes for all aspects of ways of life, human and nonhuman.

As to Arabic science I can do no better than to quote from Jim Al-Khalili’s “Pathfinders: The Golden Age of Arabic Science,” All scientists have stood on the shoulders of giants. But most historical accounts today suggest that the achievements of the ancient Greeks were not matched until the European Renaissance in the 16th century, a 1,000-year period dismissed as the Dark Ages. In the ninth-century, however, the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad, Abu Ja’far Abdullah al-Ma’mun, created the greatest centre of learning the world had ever seen, known as Bayt al-Hikma, the House of Wisdom. The scientists and philosophers he brought together sparked a period of extraordinary discovery, in every field imaginable, launching a golden age of Arabic science.

I emphasize the phrase, “… a golden age of Arabic science.”

Ken, are you sure this flourishing of Science in Islam was Arabic. I thought it was Persian.

Yes, quite certain. During the first 200 years of Islam the Caliphate in Baghdad was the center of the world and the center of remarkable scientific advances and thinking. By the 10th Century Baghdad had lost this position as three other cities became centers for science, commerce, and literature. These were Bukhara in Central Asia, the Islamic city of Cairo, and Cordoba in Muslim Spain. Much of the work, scientific and otherwise in Bukhara and Cairo was lost to later civil wars. But much from Cordoba was preserved and can be viewed and studied to this day in Spain and elsewhere.

Ken, imagination can reach back into historical contexts, especially if it is reinforced experimentally by living without electricity, sawn timber, piped water etc, helped by museum reconstructions and filming of other people’s experiments (which we in Britain are quite good at). But this the point of Chesterton’s criticism: most people never learn or have forgotten how to use their imaginations, so cannot imagine the meaning of abstract symbols nor – since we are here supposedly discussing capitalism’s growth problems – the significance of exponential growth in a finite world.

As for people being at different stages of maturity, I’ve brought up a large family and seen the order in which their facilities develop: walking, talking, developing physical and intellectual skills and applying them imaginatively. Yet we vary in where we end up: as half a century of Myers-Briggs research has shown, roughly in proportion to society’s needs inso far as education does not interfere – as it has done in Britain – by turning skilled men into poor clerks. Luckily there are only a few like me – so preoccupied imaginatively thinking of the future that I’ve lost many of my practical and social skills – and a lot like my loving and caring wife, who gets on does what she can see needs doing now. She’s not the most logical of thinkers but it takes all sorts to make a world.

Imagination is important. No historian I know can survive long as an historian without it. The biggest issue with using imagination to contextualize viewing history is finding a yard stick for assessing the results of that use. Without a realistic and fully known yardstick we run the risk of making the past look like what we today want it to look like. I offer the example of students at Princeton, Yale, etc. demanding that all past figures involved with racism and slavery be removed from the campus (e.g., John C. Calhoun’s statute, Woodrow Wilson in total, etc.). And the British (surprisingly for me) are having the same thrown at them, as students at Oxford demand that Rhodes statue be removed. If we begin imagining history this way we are on the road to a rootless future.

As to states of maturity, one example. Today Adolescence is a stage in the life of people in the west. Prior to WWII Adolescence and Adolescents did not exist. They were invented, mostly by educators and psychologists around the time of WWII. As I pointed out to one social protester who published pictures of 10-12 year coal miners in the US at the turn of the century these were not “children” as the captions of the photos claimed. Depending on location and social status childhood (really babyhood) ended around the age of 10. After that people were adults. To study and understand this process in my view is a good thing. To deny it and claim children worked in coal mines in 1910 is just plain falsehood.

When I studied the Renaissance of the 12th century for my doctorate fifty years ago I learned that most of the Islamic philosophers who influenced Europeans were Persians. So I checked the Wikepedia which says: “Most of the Islamic Philosophers are Iranian. Meanwhile, the intellectual tradition of Presia has a long history even before Islam.” Among the list of 54 Iranians mentioned is Avicenna. If it is important to us need to dig a little deeper. Remember, Persia had a long contact with Greek thought in the Hellenistic world, much longer than Arabia.

The four greatest scholars of the early era of Islam were Ibn-al-Haytham (born in present day Iraqi), Ibn Sina (born in Bukhara in present day Uzbekistan, which was part of the old Persian empire), Al-Biruni (also born in present day Uzbekistan), and the Tunisian polymath Ibn Khaldun. Yes, all serious Islamic scholars were familiar with Greek thought and teachings. They extended these greatly 700-1000 years before this was done in Europe. Some say it was these Islamic scholars that kick started the Renaissance. I tend to agree but other historians hold their judgement on this claim. But the documents clearly support the conclusion that these scholars influenced the Renaissance a great deal, even if they did not begin it. My list does not include theologians.

More from Wikepedia, Ken. “The most important scholars of almost all of the Islamic sects and schools of thought were Persian or live in Iran including most notable and reliable Hadith collectors of Shia and Sunni like Shaikh Saduq, Shaikh Kulainy, Imam Bukhari, Imam Muslim and Hakim al-Nishaburi, the greatest theologians of Shia and Sunni like Shaykh Tusi, Imam Ghazali, Imam Fakhr al-Razi and Al-Zamakhshari, the greatest physicians, astronomers, logicians, mathematicians, metaphysicians, philosophers and scientists like Al-Farabi, Avicenna, and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, the greatest Shaykh of Sufism like Rumi, and Abdul-Qadir Gilani.”

As with Greek scholarship the Islamic scholars were familiar with Persian (Iranian) scholarship, and as with that from Greece extended it vastly.

Ken, I studied Europe 1050=1350, as one of my fields for my doctorate (under Lynn White, Jr.) All medievalist when I looked at the subject 50 years ago had long put to bed the idea that the Renaissance of the 14th=15th century ended the dark ages in Europe. The Islamic influence that opened up Europe penetrated in the 12th century. So here is how I interpret what happened. The Arabic world existed on the fringes of civilization, just as did the Germanic. When Islam conquered Persia, it ran into a civilization that had long been familiar with the Greeks, and a sort of syncretism took place, where Persian civilization was absorbed into Islam. The Arabic world was the venue that provided the avenues for the dispersion of this thought to Europe and other places.

The same thing happened in the 1930s and 1940s in America. When one looks at the people from Europe who flooded into America in these years, one finds not just those who developed modern physics and the atomic bomb emigrating from Europe but many of the innovative thinker that developed postwar management science, like those who served on the Cowles Committee in the 1930s working in econometrics, or game theory, i.e., Neumann and Morgenstern. Immigrants out of central Europe provided much of the brain power for postwar dominance of American thought; the thought itself was not “American” but the venues that spread it were provided by American global economic, educational, and political power networks.

Clifford Conner does a good job I think of responding to your position.

A COROLLARY OF the Greek Miracle doctrine is that nothing of importance happened in the history of science during the so-called “Dark” or “Middle” Ages—Eurocentric terms encompassing the sixth or seventh through the eleventh or twelfth centuries C.E. The Greek legacy, the traditional story goes, was preserved by non-Aryans in the Islamic world, who merely acted as its custodians until it could be transmitted back to Aryan Europe. There, once again, Greek science could take root and grow among people who had sufficient genius to appreciate it.

This is a thoroughly misleading picture. Arabic-Islamic scholarship was not simply a passive reflection of previous Greek triumphs; it also received major inputs from Persia, India, and China and was itself a source of original contributions to scientific culture. That can be seen most clearly (but not only) in the field of mathematics. Whereas Greek mathematicians kept almost exclusively to geometry and scorned arithmetic as a tool fit only for lowly practical pursuits, Muslim mathematicians adopted the base-ten, position-value number system from India and utilized it to further mathematical knowledge in ways unimaginable to their Greek predecessors. The evidence is embedded in our language: the words “algorithm” (which meant “arithmetic” in early modern Europe) and “algebra” are of Arabic origin. The Muslims’ contribution to the development of trigonometry is preserved in the words “sine” and “cosine,” which also derive from Arabic.

Conner, Clifford D. (2009-04-24). A People’s History of Science: Miners, Midwives, and Low Mechanicks (p. 161). Nation Books. Kindle Edition.

It is true that science in the Islamic world was built on Greek foundations.

But Muslim scholars were not simply translators and copyists; they added extensive critical commentaries, sometimes based on their own original scientific investigations, to the corpus of Greek science. When scholarship in Europe began to revive in the twelfth century, the works of Aristotle and Galen recovered from Arabic sources had been refracted through the interpretive lenses of Ibn Rushd (Averroës), Ibn Sina (Avicenna), al-Razi (Rhazes), and many others. The new learning, however, rapidly hardened into an orthodoxy that hindered further acquisition of knowledge of nature. Like Aristotle and Galen, some of the Muslim savants themselves were placed on pedestals and transformed into sacrosanct authorities by European scholars. Medical school professors and elite doctors of early modern Europe, for example, treated the works of Avicenna and Rhazes as virtually beyond challenge.

The transmission of Islamic science to the West is generally portrayed as the pacific work of scholarly translators, but it was also in part an act of violent expropriation, a corollary of the war-fare that resulted in the destruction of Muslim power in Spain. “Although the lure of ancient philosophy was not the principal motive behind the West’s Crusade in al-Anadalus—crusading hysteria and an appetite for booty were more effective inducements—the acquisition of Arab learning was one of the most important results of the reconquista.

Conner, Clifford D. (2009-04-24). A People’s History of Science: Miners, Midwives, and Low Mechanicks (pp. 162-163). Nation Books. Kindle Edition.

“The Greek legacy, the traditional story goes, was preserved by non-Aryans in the Islamic world, who merely acted as its custodians until it could be transmitted back to Aryan Europe. There, once again, Greek science could take root and grow among people who had sufficient genius to appreciate it.”

This is not my position, nor that of any knowledgeable human being. Its a lot of proto-fascist bunk. I simply object to your equating Islam with Arabic and forgetting the importance of Persian and other nonArabic sources of thought i.e., as Christianity was infected with Greek thought so was Islam by Persian. Don’t call Iranians Arabs, it won’t wash. And you still have to explain why in the 12th century Renaissance in Europe the reawakening of learning provided such a continuous stimulus to the West and did not do so in Islam. I lectured on it in my courses on World Civilization, because it is an unavoidable topic, if people want to understand the modern world. One great difference in the West was the rise of the university, as an oasis that could defy religious fanaticism (Reason and Revelation in the Middle Ages) and autocratic power, another Feudalism, another the extraordinary growth of medieval technology and agricultural productivity that spurred the expansion of life and work in the middle ages, led by religious orders. Look inside Medieval European civilization, for answers about dynamism, not to Islam.

My apology. I totally misunderstood your concerns. You are correct that Persians (Iranians) are not Arabs. My point is that all these scientists were Muslim scientists. Part of a scientific golden age that was created during the first 300 years of the Islamic Empire. Thus, Islamic Science. As to the your other assertion that the dynamism of learning and science in Europe was due to Medieval European civilization and that Islam provided no such kick to dynamic growth in knowledge and learning. First, let’s get the timeline straight. Those invasions from Europe to Islamic territory called collectively the “Crusades” lasted from 1000 to 1500. The Ottoman Empire, asserting to speak for Muslims began about 1300 and disintegrated after WWI. European colonialism in the Middle East began about 1800 (although British and French interfered with all aspects of Middle Easter life as far back as 1580. So like China the tinkering and outright imperialism of the European powers were a constant disruption of government, economics, science, literature, engineering, and the arts in the Islamic lands from 1000 till 2016. No surprise the Islamic nations had trouble with progressing in all these areas over that period. Second, as the passage earlier quoted points out, “When scholarship in Europe began to revive in the twelfth century, the works of Aristotle and Galen recovered from Arabic sources had been refracted through the interpretive lenses of Ibn Rushd (Averroës), Ibn Sina (Avicenna), al-Razi (Rhazes), and many others.” But as with Aristotle and Galen, the Islamic scholars were hardened into an unchangeable orthodoxy by Europeans. So learning was going nowhere fast in Europe. What changed this was the invention of capitalism and its oppositions, the work of technologists, mechanics, agriculturalists, etc. who were not accepted or recognized as scholars by the elitist science of the times, the work of those who rejected the overly “mathematical” focus of accepted science, Francis Bacon was particularly diligent in pointing out science would be revitalized by basing in on craftsmen’s knowledge of nature. He also declared the university-based sciences “stand like statutes, worshiped and celebrated, but not moved or advanced, while the ‘mechanical arts … having in them some breath of life, are continually growing. Simply put, it was the folks who had to make things work on a daily basis who made European science dynamic and forced it to continually expand its knowledge areas and accumulation. Despite what some historians claim the expansion of knowledge and learning in Europe beginning in the 12th century was helped only marginally by men Kepler, Copernicus, Galileo, and Newton.

“Francis Bacon was particularly diligent in pointing out science would be revitalized by basing in on craftsmen’s knowledge of nature. He also declared the university-based sciences “stand like statutes, worshiped and celebrated, but not moved or advanced, while the ‘mechanical arts … having in them some breath of life, are continually growing. Simply put, it was the folks who had to make things work on a daily basis who made European science dynamic and forced it to continually expand its knowledge areas and accumulation.”

We certainly have to get our time=lines straight. In their academic traditions Germans talk about Lehr-und Lernfreiheit, by which they mean, the independence of the knowledge community from interference by religion or state, in its pursuit of knowledge. When the state interfered, as in National Socialism, people fled and knowledge creation ceased. That is what I meant about the importance of a feudal tradition in Europe, which developed into the Wissenschaft tradition, where a community of researchers assumed the responsibillity, in free and open debate, of advancing knowledge.

You don’t have to wait for Francis Bacon to learn about practicality and scientific method. Roger Bacon, and Robert Grossteste stressed empiricism as opposed to rationality in the 13th century, in a university world where ideas travelled freely. R. Bacon summarized his belief clearly: “Neither the voice of authority nor the weight of reason and argument are as significant as experiments from which come peace to the mind.” It was not just a constant triumph of enlightenment because academic infighting has been a nasty business throughout and so has religious (Galileo) and state interference, but when science fused with technology in the 19th century, the university had to be added as a knowledge creating community to practical men in the mechanical arts.

Allow me to get a few things out of the way. First, there is no “scientific method.” There are multiple ways to approach revealing an object of study. Mathematics can play a role, albeit a small one. So can axioms and presuppositions. But again a small role. The heart of doing science is observation, in as many forms and with as many tools as the work requires or can be made available. I want to emphasize that observation is not one thing but many. From human senses alone to electronic and non-electronic instruments, laboratory experiments, etc. Linking the observations is vital, but should always retain the data from observations. Second, there is a scientific community but it’s much larger and more eclectic than your comments would admit. And that brings me to my primary point. From its beginnings in ancient Greece science has been and remains a “club for professional intellectuals.” No blue collar, no artisans, mechanics, etc. need apply. In fact, scientists look right through and over such persons. Science historian William Eamon notes this, “…printing technology and popular culture had as great, if not stronger, an impact on early modern science as did the traditional academic disciplines.” It was indeed the Greeks who invented science as we know it today. An elitist enterprise that would have gone nowhere had the non-elite workmen, agriculturalists, mechanics, tanners, dye makers, etc. not kept it going and expanding. Aristotle, an important source for European science was like his teacher Plato a non-empiricist. Answers to questions about the world were according to these scholars to be found in books or via abstract a priori reasoning. Both the elitism and non-empirical path continues in science today. If you don’t believe me go to any meeting of the American Physical Society.

Ken, “What changed this was the invention of capitalism and its oppositions, the work of technologists, mechanics, agriculturalists, etc. who were not accepted or recognized as scholars by the elitist science of the times, the work of those who rejected the overly “mathematical” focus of accepted science, Francis Bacon was particularly diligent in pointing out science would be revitalized by basing in on craftsmen’s knowledge of nature”.

Agreed, Ken – and thanks, Bob, for your gloss on this – but what’s changed? I’ve belatedly continued this because it seems to me elite scholars still think science is about acquiring knowledge for its own sake, not for Bacon’s “the glory of God AND the relief of Man’s estate”. Shades of American students of history wanting memorials of slavers removed: where I live is still littered with the ruins of exemplary and evolving monastic agricultural communities actually destroyed by Henry VIII over 150 years before capitalism proper began, with its “Glorious Revolution” and the founding of the Bank of England. The Middle East had its own contacts with Greek science, but by around 400 a.d., a thousand years before the invention of printing, the by then Christian records of Greek and Roman science had been destroyed by the iconoclasts who burned down the great library of Alexandria. In the aftermath of the fall of Rome around 150 years later, St Benedict was therefore starting afresh, taking the communal survival economy, recorded in the Acts of the Apostles, from fugitives living in holes in the ground to the exemplary agriculture, artistic crafts etc and magnificent Gothic architecture which, unlike the soaring tower blocks of Modernist individualism, are still being rebuilt after being so regularly knocked down.

I think what hasn’t changed is sane people still being attracted to and grateful for goodness, beauty and truth rather than the self-service of money-loving idiots, with inexperienced youngsters still being corrupted and driven insane by the lure of fools gold and the elegant packaging of poisonous rubbish (“Satan’s mask of respectability”).

Lost part of the first sentence when I moved it. Should read, “What changed this was the invention of capitalism and its oppositions, newer versions of democracy, the work of technologists, mechanics, agriculturalists, etc. who were not accepted or recognized as scholars by the elitist science of the times, the work of those who rejected the overly “mathematical” focus of accepted science.” As to the path of Greek scholarship. Yes, a lot was lost when the Alexandria Library was burned. But most was saved and extended by Islamic scholars, who also absorbed and extended elements of Chinese and Persian learning and teaching. This would have had a more positive outcome in Europe had not European science ossified into a fixed hierarchical elite intellectualism, which was passed along to the so called fathers of current science — you know Galileo, Kepler, Copernicus, Newton, etc. And that elitism and intellectualism just keeps chugging along right up to 2016.

Sorry Ken, so many misconceptions about science on this site.

“Aristotle, an important source for European science was like his teacher Plato a non-empiricist. Answers to questions about the world were according to these scholars to be found in books or via abstract a priori reasoning.”

Then they were not scientists.

“The heart of doing science is observation”

No, observation is essential to science, but it is not the heart of science.

Once again here are the steps in science:

1. Perception of some kind of regularity in observations. Note *perception*, a non-rational process of cognition.

2. Formal description of the pattern – could be in words or mathematical relationships. This is “hypothesis”. Some people call the components of the hypothesis “axioms”, but this is a mis-use of a term in logic. One can call the components “assumptions” – about how the observable world might work.

3. Deduction of implications from the hypothesis. Logic, and possibly mathematics, is used here. Mathematics may be very simple of very elaborate, but this is not a criterion for judging a hypothesis.

4. Comparison of implications with more observations. This is “testing”.

Testing may or may not be definitive, and the process may iterate many times, refining hypotheses, refining deductions from the hypothesis, and refining observations.

A hypothesis that has passed significant tests may be called a “theory”, but there is no rigorous criterion for this. Einstein’s theory of gravity, notwithstanding gravity waves, may still be found to be inadequate for some purposes. That would not make it “wrong” or “disproven”, it would merely limit the range of its usefulness.

https://betternature.wordpress.com/2014/03/05/a-science-of-economies/

Ken, about that gap between practical men and science.

The Association of German Engineers (Verein Deutscher Ingenieure, VDI), founded in 1856, consistently pitched a large tent that included machinists and craftsmen in its ranks. Academic degree holders were also members; an engineering professor from a technische Hochschule usually presided, so that VDI membership assembled a great chain of talent from the tacitly educated artisan worker who had learned his craft in apprenticeship programs and in technical schools to the engineering professor working in a Hochschule research institute, an ensemble that united the Können (skill) of the practical world with the Wissen (explicit knowledge) of science.

According to the sociologist Ian Glover: “In Anglophone countries, two cultures, the arts and sciences are recognized.” In the two cultures engineering is placed under science but in an inferior place, In the UK scientists, say physicists, look down on engineering as an inferior subject for the less brilliant and gifted. Glover went on to note that in [Germany] rather than two cultures there are three: “Kunst (like the arts), Wissenschaft (similar to science) and Technik (the many engineering and other making and doing subjects, representing practical knowledge (Können),” but including scientific knowledge (Wissen) that the technical institutes added in the second half of the century.

We have known about this for a long time, Ken. I wrote my first article on it, myself, in 1977.

Your description of how science and scientists work is just for textbooks and public relations. I suggest you take a look at “Science in Action” by Bruno Latour or the most recent edition of the “Handbook of Science and Technology Studies.” These provide actual empirical descriptions of the actual work of scientists. That work bears little resemblance to the idealized picture you present.

Second, three examples. Are they science and are those performing them scientists. Let’s stick to the European Medieval period for now. An armorer creates a new long bow (new materials, new design, new usage instructions) and then tests in capability to penetrate breast plates and other body armor and it accuracy over ranges up to 500 yards. Is the armorer a scientist? Next, a perfumer creates a new blend never seen before. And then investigates its effects on love and marriage among several groups of non-noble people of between 15 and 25 years of age. Is the perfume blender a scientist? An experienced farmer measures wind, rain, hours of sunshine and uses that information to guide his planting and harvesting decisions. Is the farmer a scientist?

Nonsense, Ken. My description of the fusion of German science and practicalitiy is based on years of studying the subject while living in German communities and seeing it in action.

You need to be more specific about what’s nonsense. As to Germany, I’m a dual citizen US and Germany. I know Germany well. Obviously I didn’t live there as long as you did. But we can debate that another time. Science is what scientists do. If you follow their actions, that’s science, right? If that’s correct then scientists’ actions don’t look anything like the formal steps and process you outline. I’ll go with the actual observed actions. But on your side there are fewer studies on German scientists. So I’ll leave open that they act differently than American, British, and French scientists.

Did you get the concept of Technik, as a third science, distinct from science and the arts, Ken. That idea people talked about as a new civilization, in the late 19th century. Technik is expressed in Germany today in the Frauenhofer Societies as distinct from the Max Planck Institutes. And in the prestige that craftsmanship has in the society, where 40% of the kids enter apprenticeship programs in their 10th years of high school education. I remember, when my children’s friends at the Gymnasien entered these programs, feeling sorry for them for not going on for a university degree, only to discover that entering an apprenticeship program was not a pejorative step in German society. When a person earns an apprenticeship or better still acquires a Meisterbrief, it is announced in the newspapers.

Yes, I understand the notion of Technik. My four cousins in Munchen are split along these lines. Two are engineers at Siemens; two work on the floor at BMW.

Economics’ methodological problem

Comment on ‘Capitalism’s growth problem’

When economists, who after more than 200 years have not figured out what exactly the difference between profit and income is, talk about science and logic things become a bit surreal.

One outstanding characteristic of Heterodoxy in particular is that deductivism or the axiomatic-deductive method is abhorred. Consequently, other methods are proposed. One among others is abduction (see Lars P. Syll’s blog https://larspsyll.wordpress.com/2016/02/13/why-science-necessarily-involves-a-logical-fallacy/).

This, to be sure, is perfectly legitimate. The question is this: if the abductive method is indeed superior, why not apply it and present concrete results? Success is the best argument. To recall, it were the discoveries of Galileo, Newton or Einstein which cemented the reputation of the axiomatic-deductive method. This method sums up the personal experience of genuine scientists and postulates the primacy of theory over naive empiricism: “This indicates that any attempt logically to derive the basic concepts and laws of mechanics from the ultimate data of experience is doomed to failure.” (Einstein, 1934, p. 166)

It is a remarkable coincidence that Einstein deduced gravity waves from his theory in 1916 and in our days, 100 years later, they are observed. This success is a fine specimen for the primacy of theory and a smashing refutation of naive empiricism.

In marked contrast, abduction postulates the primacy of empiricism: “In inference to the best explanation we start with a body of (purported) data/facts/evidence and search for explanations that can account for these data/facts/evidence.” (See LPS blog)

Now, the fundamental problem is that this may even work satisfactorily on a small scale, but the subject matter of economics is the economy, or more precisely, the world economy. Clearly, the world economy as such cannot be seen or experienced, so there is no other way than to start with a theoretical picture as a first approximation. And this is exactly what Popper has said “And in the social sciences it is even more obvious than in the natural sciences that we cannot see and observe our objects before we have thought about them. For most of the objects of social science, if not all of them, are abstract objects; they are theoretical constructions.” (1960, p. 135)

Here again we have the primacy of theory. Popper, of course, was not the first to realize this, he got it from an economist: “Since, therefore, it is vain to hope that truth can be arrived at, either in Political Economy or in any other department of the social science, while we look at the facts in the concrete, clothed in all the complexity with which nature has surrounded them, and endeavour to elicit a general law by a process of induction from a comparison of details; there remains no other method than the à priori one, or that of ‘abstract speculation’.” (Mill, 1874, V.55)

Like nothing else, ‘abstract speculation’ puts the heterodox economist’s teeth on edge. The horror association is the absolutely vacuous formal exercise of general equilibrium theory. This green cheese nonentity, though, is clearly NOT what Mill had in mind when he spoke of ‘abstract speculation’. For him facts had always the last word “The ground of confidence in any concrete deductive science is not the à priori reasoning itself, but the accordance between its results and those of observation à posteriori.” (Mill, 2006, p. 896-897)

The axiomatic-deductive method implies that the ultimate criterion for the assessment of a theory is empirical proof/refutation. The methodological blunder of standard economics has never been ‘abstract speculation’ but ‘empirically vacuous speculation’ of the type how-many-angels-can-dance-on-a-pinpoint.

The axiomatic-deductive method was never meant to be a fact-free logical exercise. It was Debreu who pushed it down this blind alley. It is fully justified to reject Debreu’s misapplication, but this gives one no good reason to relinquish the method.

So there is no real need to invent a new method for economics. The scientific method is well-defined and applies here as well “Research is in fact a continuous discussion of the consistency of theories: formal consistency insofar as the discussion relates to the logical cohesion of what is asserted in joint theories; material consistency insofar as the agreement of observations with theories is concerned.” (Klant, 1994, p. 31)

Logical consistency is secured by applying the axiomatic-deductive method and empirical consistency is secured by applying state-of-the-art testing.

Economics never rose above logically and empirically inconsistent speculation and storytelling. Therefore, it has not and cannot solve the growth problem or any other vital economic issue.

Egmont Kakarot-Handtke

References

Einstein, A. (1934). On the Method of Theoretical Physics. Philosophy of Science, 1(2): 163–169. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/184387.

Klant, J. J. (1994). The Nature of Economic Thought. Aldershot, Brookfield, VT: Edward Elgar.

Mill, J. S. (1874). Essays on Some Unsettled Questions of Political Economy. On the Definition of Political Economy; and on the Method of Investigation Proper To It. Library of Economics and Liberty. URL http://www.econlib.org/library/

Mill/mlUQP5.html#EssayV.OntheDefinitionofPoliticalEconomy.

Mill, J. S. (2006). A System of Logic Ratiocinative and Inductive. Being a Connected View of the Principles of Evidence and the Methods of Scientific Investigation, volume 8 of Collected Works of John Stuart Mill. Indianapolis, IN: Liberty Fund.

Popper, K. R. (1960). The Poverty of Historicism. London, Henley: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Let’s talk about “theoretical constructions.” Popper’s mistaken passes on an error that existed before him and that he foisted off on others. That error is that only smart people, i.e. the intellectual elite, scientists create these constructions. Actually, in both the so called natural and so called social sciences these constructions are created first by non-scientists and then later by scientists. Economists did not create the world, or even the national economy. That job was done by business persons of all types, by politicians, by accountants, by engineers, by teachers, etc. Then economists came along and took on the “responsibility” of determining who was correct and who incorrect, and of fixing the construction. Not that the original constructions needed fixing. Physical scientists did the same. Did marine navigators need scientists to tell them the world was round? No. Did catapult builders need scientists to tell them force=mass x velocity? No. But okay multiple constructions about the same events can be dealt with. Scientists, however insisted that the constructions they did not built are wrong and must be rejected. It’s an old story in science and with scientists. No cooperation or collaboration. That’s what I mean by elitist intellectualism.

Sorry, Geoff. If you had said there are so many “inadequate conceptions” rather than “misconceptions” of science on this site I would have found it easier to agree with you, though on the whole I do.

When you start asking whether Aristotle was a scientist or not you yourself have immediately fallen into the trap of implying what Ken goes on to assert: “science is what scientists do” (of a time when science meant knowledge and Aristotle was referred to as a philosopher), when the point at issue is “what is a scientist?” The problem with that argument is that scientists lose interest in problems that have already been resolved, and despite half the job of scientists being teaching science (Bacon’s encyclopedia, passing on solutions to future generations) and Kuhn’s distinction between revolutionary (fundamental) and normal (applied) science, your four steps in scientific method, Geoff, cover only critical realist Roy Bhaskar’s fundamental DREI(c) phase of science and not his RRREI(c) applied phase. (“Dialectic: the Pulse of Freedom”, 1993, Verso, pp. 109, 133-4).

My version of Bob Locke’s 1977 defence of practical knowledge was a 1969 letter in my then professional journal, pointing out that we are psychologically and in practice specialists, with the lead in the four phases of your scientific method often being taken by different people, and (as Bhaskar attempts to explain, ibid. 134) seeking causal explanations at lower levels of realisation (c.f. animals > cells > molecules). Hence there can be a scientific interest in engineering and technology as well as in fundamental science, and people with problem-solving curiosity whose overt job and training is in at any of these levels and phases of discovery. In practice the separate labels scientist, technologist and engineer have given rise to misleading impressions and demarcation disputes. It would be better to have some compound term, for which I humorously suggested “scinoleers” – fully appreciating it might get pronounced “skin-o-leers”! In that context I couldn’t extend the argument to cover social science.

A few years later, after immersion in the four level structure of the Algol68 scientific programming language and an introduction to Shannon’s switching circuit digital logic, analogue error correction logic and information theory, I began to see society as being all about communication, so that for each level of physical realisation there was a level of what Bhaskar called Identification (the ‘I’ in DREIC(c) and RRREI(c)). Here a new type of whole emerges when all four are complete, as when a clock’s rotating through four quarter-hours represents an hour which represents them all; or put the other way, the reality both represents itself and is what it does. Still long before Tony Lawson introduced me to Bhaskar’s work, what I was saying to a Chestertonian friend (sadly “late”) reminded him of Arthur M Young’s “The Geometry of Meaning” (1976, RBA) which by coincidence his father had published.

This clock example corresponds mathematically to the operator i (for imaginary) rotating a one-dimensional line through a right angle in two-dimensional space; it turns out the units of integer arithmetic are a special case constructed by abstraction from complex numbers just as dumb Economic Man was constructed by abstraction from Real Man: an animal with four functional parts to its brain. A more accurate mathematical combination of the objects and operations I am talking about is given by Hamilton’s quaternions, in which three operators, i j and k, rotate a two-dimensional plane through three different right angles, and a fourth, the combination of i j and k, inverting the inversion of the plane resulting from those operations to end a complete cycle of six operations by getting back where we started.

And so we get back to Geoff’s four phases of the scientific method. They involve not just a daisy chain loop of four functions possibly performed by four specialists, but also two more functions linking the functions not otherwise directly connected. Thus I was working in the experimental phase, but thereby seeing its problems directly and possible solutions intuitively, i.e. retroducing to the hypothetical phase without needing to go through formal deductive evaluation and further research. Which is much what Bob Locke was saying about the value of practical knowledge.