But more of what?

Source: Nitzan and Bichler, Capital as Power

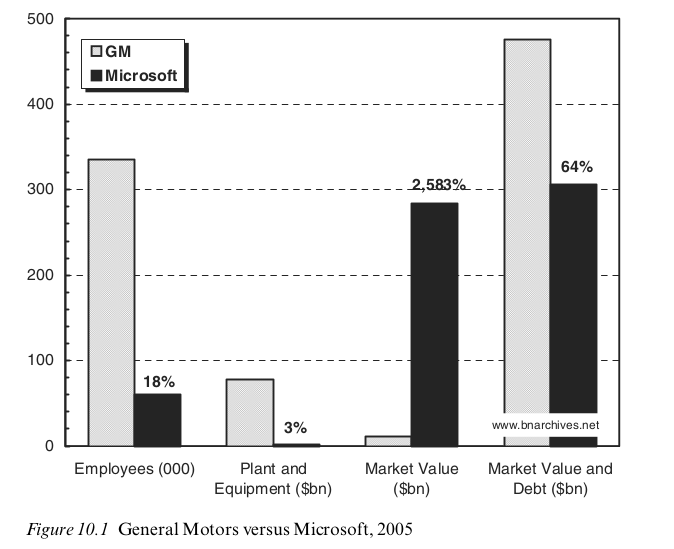

In 2005, Microsoft’s market value was 2,583% greater than that of General Motors. Mainstream economists would say that Microsoft therefore had more property than GM. But more of what? Nitzan and Bichler point out that when we look under the hood of market value, there’s nothing ‘real’ to back it up. Microsoft, for instance, has only 18% as many employees as GM. And it owns only 3% as much equipment (in dollar terms).

So is this a distortion? Is it a sign that Microsoft’s wealth is fictitious? No, say Nitzan and Bichler. Wealth isn’t about material property. Instead, they argue that wealth is a commodification of property rights. So Microsoft’s greater market value stems from its greater ability to convert property rights into income. That Microsoft can do this without owning bricks and mortar is interesting, but not surprising. As intellectual property teaches us, property rights need not be attached to anything physical.

An obvious point: market value is not determined by the disposal value of a firm’s assets, physical or intellectual. It is supposed to be determined by the future profits a firm is expected to make as a going concern. The expectation is that these profits will be distributed among shareholder either as dividends or as an appreciation in the value of their share-holdings. Saying “So Microsoft’s greater market value stems from its greater ability to convert property rights into income.” is true but an odd way to put it. Microsoft’s dominant position in a growing business sector means its income prospects exceed those of GM which has a more contestable position in a sector facing disruptive change. Those different income prospects are what confer different value on the property rights each company possesses. Nor is it clear that all of a firm’s characteristics or assets, which affect its income prospects, can be boiled down to property rights. A firm has no rights in skilled personnel, for example but they may be key to its prospects.

I think that the issue here is (1) that what matters to capitalists is capitalization rather than the ‘real capital stock’, and (2) that capitalization is determined not by ‘productivity’ but by the effect of power on future earnings, hype and risk.

Otherwise, we would have to conclude either that MS’s capital stock is 86,100 more productive than GM’s (=2583/0.03), that its employees are 14,350 more productive (=2583/0.18), or some combination of the two.

“A firm has no rights in skilled personnel” I remember seeing a film about Steve Jobs, how he and other tech giants had reached an agreement about not hiring people leaving his company. Reciprocated amongst themselves. Never punished, Never stopped. What do you call that? I call it raw power. The establishment of a exclusionary right in fact.

What explains our everyday economic actions? How and why do we spend, misspend, save, invest, or gamble away our monies? Do women and men treat money differently? Why is it, for instance, that women are more likely to allocate the household’s money to children, as compared to men’s allocation of similar resources? What accounts for the fact that even among the most loving couples, partners often conceal or misrepresent their earnings or expenditures?

All of us regularly confront a whole range of such puzzling economic dilemmas. Many of them involve our most intimate ties: should we help our adult child with his or her finances, and if so, for how much and how long? How and for whom should we spend the tax rebate or income tax refund? When should we write our wills? How can we manage the care of an aging parent without losing our jobs? What do we owe our uninsured mother-in-law who needs expensive medical treatment? Does the sibling who cares for our parent have a greater right to that parent’s inheritance?

Our responses are not always consistent. Why, for instance, do people often react with disgust or discomfort at efforts to set a monetary value on human life, yet embrace life insurance and multiple other legal arrangements for compensating with cash the injury or loss of life? For less daunting quandaries, think of routine gift-giving dilemmas: when, for instance, are gifts of cash appropriate and when are they tacky? When does offering a gift certificate offend the recipient?

The search is on for superior explanations of these and many other features of our economic lives. Impatient with standard accounts of economic action as inexorably driven by calculating self-interest, in the past few decades scholars from a range of disciplines have proposed dazzling new understandings of economic activity. Turning away from abstract theories and plunging into the messiness of actual economic practices, sociologists, anthropologists, psychologists, and others are slowly but surely revolutionizing how we understand life’s commerce. From different perspectives, these scholars expose a rigid concept of “homo economicus” as a rusty, old-fashioned notion ready for retirement. Even some economists, while fully embracing rational choice models, have broadened their vision to provide often surprising and instructive explanations for the economics of everyday life.

The serious political implications of the challenge to standard economics became clear in 2008. The financial debacle that jolted the world painfully dramatized the need for new macroeconomic ideas. The crisis not only upset economic institutions and practices but radically undermined prevalent understandings of how economies work. The fantasy that real contemporary capitalist systems have perfectly free markets and that these can produce the best of all possible economic worlds crumbled along with the speculative, unregulated market policies and products it had spawned. Even the staunchest free-market advocate, Alan Greenspan, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, famously conceded in October 2008 before the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform that he had “found a

flaw” in his free-market ideology.

Following on, in 2009, the Obama administration paid close attention to the strategic alternative insights of behavioral economists such as Richard Thaler. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein’s Nudge (2008), along with George A. Akerlof and Robert Shiller’s equally influential Animal Spirits (2009), further extended the public debunking of neoclassical orthodoxy. In July 2009, even the Economist’s cover proclaimed, “Modern Economic Theory: Where It Went Wrong—and How the Crisis Is Changing It.”

Out of the spotlight, anthropologists and sociologists were showing that personal choice and incentives explain only a portion of economic actions. Our relations to others becomes the centerpiece of such actions. Our economic actions, anthropologists and sociologists insist, remain mysterious or may even appear to be irrational until we understand that they exist within dense webs of meaningful relationships.

One cannot predict actions from individual preferences alone, because people are constantly negotiating those preferences in their interactions with others. As a result, when we replace theories of individual rationality with theories of individual irrationality, we just introduce a different kind of problem. We need to probe further into the communal relations that often help us decipher and explain seemingly irrational preferences. Instead of irrationality, we discover variable forms and definitions of what constitutes both rationality and self-interest. Such variation often hinges on the communal interactions in which economic action involves us. What determines, for instance, the kind of collective relations that people establish for different sorts of economic transactions, such as buying a used car or renting an apartment? Conversely, how do the kinds of relations already existing among the parties to an economic action affect its character and outcome? When buying a house, what difference does it make

if buyer and seller are kin, friends, or strangers connected by a real estate agent? In each case, how and what we define as rational action will vary significantly.

With a focus on such communally based questions and drawing from a range of theoretical frameworks, in the past thirty years or so anthropologists and sociologists have created a set of important alternative explanations of economic activity. Relying on an increasingly broad spectrum of methods, from sophisticated network analyses to rich ethnographic observation, economic anthropologists and sociologists offer revealing accounts of how economic organizations and activities actually work.