Devaluation devaluated? J.W. Mason on Asia.

One of the reasons (if not THE reason) why economists advise countries to devalue their currency is the idea that lowering the domestic price level will lead quite fast to higher net and gross exports and therewith to growth, higher employment and lower unemployment. But does it? In a blogpost J.W. Mason pointed out that in the case of external devaluation (and internal devaluation seems to work even worse) this did not happen in Asia after the 1997/1998 crisis. Recently he used some growth accounting data constructed by Enno Schröder, which in the words of Mason ‘are tremendously important results‘, to shed more light on this question. His conclusions:

Even a very deep devaluation, as in Indonesia, is not guaranteed to change the relative prices of a country’s imports and exports.

Even if a devaluation is passed through to relative prices, as in Thailand, price elasticities may not be large enough to produce a favorable change in the trade balance.

Even if a devaluation moves relative prices, and demand is price-elastic enough for the price change to move the trade balance in the right direction, as in Korea, a short-term improvement in competitiveness may not persist.

When countries do achieve a long-term improvement in competitiveness, like Malaysia, they don’t necessarily do so through a relative cheapening of exports compared to imports. On the contrary: If the Marshall-Lerner condition is not satisfied, then a relative increase in the price of a country’s exports will raise export earnings. In the case of Malaysia, improved terms of trade (that is, a rise in the price of its exports relative to its imports) account for about half the long-run improvement in its trade balance.

The Asian precedent does not make a Greek (or Spanish, or Portuguese, or Irish) devaluation look like an obviously good idea.

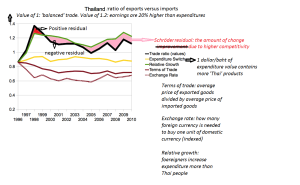

These conclusions are based upon graphs like these which show the contributions of lower export income due to lower export prices (solid brown line), higher net exports due to lower domestic demand relative to foreign demand (green line), changes in the ‘import content’ of domestic and foreign demand (i.e. how much of every bath/dollar/euro of expenditure is spent on imported stuff) and changes in competitivety which shows as a residual (complicating text added by me):

As I see it his view is consistent with the vision that exporting companies are parts of global production clusters and chains which are only to a quite limited extend influenced by changes in costs in a particular country but whose sales are, of course, influenced by foreign demand, while imports can to quite some extent be explained by assuming that domestic demand in many countries knows a rather stable ‘import coefficient’ in combination with a very difficult to change ‘export orientation’ of the domestic economy which is not so much based upon low wages but upon good and ever improving products and services and unique selling points.

Why is there a link to http://www.greeka.com/cyclades/cyclades-beaches.htm???