Archive

The awakening of an econ student

from carmeloferlito

I became an economist by mistake. The malicious will say that you can deduce it from the quality of my writings. I like to believe in the bizarre paths of Destiny on which the flights of human liberty stumble along.

Here I would like to link my personal experience – of little interest to the reader – to the far more interesting subject of the ongoing debate in economic science. Indeed, as is well known, particularly since the crisis began in 2007, a certain disillusionment has been growing about economists’ ability to foresee the course of events. While asking economists to foresee something perhaps pushes them into the sphere of magic to which they do not belong, there is strong discontent with their ability to explain events in progress. If the beautiful and highly formal mathematical models developed over the course of decades do not serve to predict the future – and it astonishes me that someone might believe that – they lack ex-post usefulness in interpretation. In short, they are not very useful. read more

Anti-Cash-Alliance suffers setback in their home-town New York

from Norbert Häring

The Better Than Cash Alliance (Visa, Mastercard, Citibank, Bill Gates, USAID) coordinates the global war against cash from New York. Now, the city council of the headquarters of the Alliance has decided to oblige all brick and mortar stores and restaurants to accept cash. The justification of the regulation is a low blow for the alliance’s financial inclusion propaganda.

According to a USA-Today report, retail stores, restaurants, and bars will have to accept cash in the future. The new regulation gets in the way of a program of credit card company Visa, which is paying restaurants for going completely cashless.

Visa is one of the founding members of the Better Than Cash Alliance, which aims to eliminate cash worldwide. The alliance is based in New York. With generous donations, it obtained office space from the United Nations Capital Development Fund (UNCDF) and now misleadingly calls itself a “UN-based organization”. Read more…

On causality and econometrics

from Lars Syll

The point is that a superficial analysis, which only looks at the numbers, without attempting to assess the underlying causal structures, cannot lead to a satisfactory data analysis … We must go out into the real world and look at the structural details of how events occur … The idea that the numbers by themselves can provide us with causal information is false. It is also false that a meaningful analysis of data can be done without taking any stand on the real-world causal mechanism … These issues are of extreme important with reference to Big Data and Machine Learning. Machines cannot expend shoe leather, and enormous amounts of data cannot provide us knowledge of the causal mechanisms in a mechanical way. However, a small amount of knowledge of real-world structures used as causal input can lead to substantial payoffs in terms of meaningful data analysis. The problem with current econometric techniques is that they do not have any scope for input of causal information – the language of econometrics does not have the vocabulary required to talk about causal concepts.

What Asad Zaman tells us in his splendid set of lectures is that causality in social sciences can never solely be a question of statistical inference. Read more…

Political Economy?

from Peter Radford

“American economics harbors fierce political debates over theory, methodology, and policy. In practice and in comparative perspective, however, the main trend over the course of the twentieth century has been the standardization of training as well as a homogenization of evaluation criteria that has marginalized nonorthodox approaches. After institutionalism was dethroned by the rise of mathematical economics and more politically challenging forms of intellectual heresy (such as Marxism) were relegated to peripheral institutions and sometimes to other disciplines, American economists installed themselves confidently within the neoclassical paradigm. It is within this paradigm that the major intellectual debates have taken place. … In other words, the dominant conversations within the discipline have centered around which hypotheses in the neoclassical framework may be modified or tweaked to account for observed empirical patterns. But American economists implicitly agree to keep disturbances to a minimum; as a result the framework is almost never questioned as a whole.”

That’s a long quote from Marion Fourcade’s excellent study of the discipline of economics “Economists and Societies” published in 2009. I think it helps us wrap our minds around why it has taken so long for any discernible change in the profession’s thinking to have seeped into the open. Read more…

Experiments in social sciences

from Lars Syll

How, then, can social scientists best make inferences about causal effects? One option is true experimentation … Random assignment ensures that any differences in outcomes between the groups are due either to chance error or to the causal effect … If the experiment were to be repeated over and over, the groups would not differ, on average, in the values of potential confounders. Thus, the average of the average difference of group outcomes, across these many experiments, would equal the true difference in outcomes … The key point is that randomization is powerful because it obviates confounding …

Thad Dunning’s book is a very useful guide for social scientists interested in research methodology in general and natural experiments in specific. Dunning argues that since random or as-if random assignment in natural experiments obviates the need for controlling potential confounders, this kind of “simple and transparent” design-based research method is preferable to more traditional multivariate regression analysis where the controlling only comes in ex post via statistical modelling.

But — there is always a but … Read more…

A stock market boom is not the basis of shared prosperity

from Thomas Palley

The US is currently enjoying another stock market boom which, if history is any guide, also stands to end in a bust. In the meantime, the boom is having a politically toxic effect by lending support to Donald Trump and obscuring the case for reversing the neoliberal economic paradigm.

For four decades the US economy has been trapped in a “Groundhog Day” cycle in which policy engineered new stock market booms cover the tracks of previous busts. But though each new boom ameliorates, it does not recuperate the prior damage done to income distribution and shared prosperity. Now, that cycle is in full swing again, clouding understanding of the economic problem and giving voters reason not to rock the boat for fear of losing what little they have.

The Groundhog Day boom-bust cycle links with John Kenneth Galbraith’s observations on the phenomenon of financial fraud via embezzlement, which he termed “the bezzle”: Read more…

Why all RCTs are biased

from Lars Syll

Randomised experiments require much more than just randomising an experiment to identify a treatment’s effectiveness. They involve many decisions and complex steps that bring their own assumptions and degree of bias before, during and after randomisation …

Some researchers may respond, “are RCTs not still more credible than these other methods even if they may have biases?” For most questions we are interested in, RCTs cannot be more credible because they cannot be applied (as outlined above). Other methods (such as observational studies) are needed for many questions not amendable to randomisation but also at times to help design trials, interpret and validate their results, provide further insight on the broader conditions under which treatments may work, among other rea- sons discussed earlier. Different methods are thus complements (not rivals) in improving understanding.

Finally, randomisation does not always even out everything well at the baseline and it cannot control for endline imbalances in background influencers. No researcher should thus just generate a single randomisation schedule and then use it to run an experiment. Instead researchers need to run a set of randomisation iterations before conducting a trial and select the one with the most balanced distribution of background influencers between trial groups, and then also control for changes in those background influencers during the trial by collecting endline data. Though if researchers hold onto the belief that flipping a coin brings us closer to scientific rigour and understanding than for example systematically ensuring participants are distributed well at baseline and endline, then scientific understanding will be undermined in the name of computer-based randomisation.

The point of making a randomized experiment is often said to be that it ‘ensures’ that any correlation between a supposed cause and effect indicates a causal relation. This is believed to hold since randomization (allegedly) ensures that a supposed causal variable does not correlate with other variables that may influence the effect.

The problem with that simplistic view on randomization is that the claims made are both exaggerated and false: Read more…

The WHY of crazy models

from Asad Zaman

I was professionally trained as an economist, and learned how to build models with the best. As described in detail in a previous post on “The Education of An Economist“, it was only by accident that, a long time after graduate school, I learned of glaring conflicts between the theory I had been taught, and the historical evidence about effects of free trade and trade barriers. Further exploration along this direction dramatically widened the chasm between the economic theories I had learnt, and the historical and empirical evidence all around me. This led me to a set of puzzles which I have been struggling with for the past two decades. [1] Why is that economists are not aware of the conflict between economic theories and empirical evidence? [2] Why is it that economists do not care, when such conflicts are pointed out to them? In “Trouble With Macro“, Romer expresses these same two points as follows: “The trouble is not so much that macroeconomists say things that are inconsistent with the facts. The real trouble is that other economists do not care that the macroeconomists do not care about the facts. An indifferent tolerance of obvious error is even more corrosive to science than committed advocacy of error.”

Once we move from the easy-to-establish fact that economists use crazy models, to the much more difficult meta-question of WHY economists use crazy models, one apparently obvious answer suggests itself: read more

Reducing the health-care tax

from Jared Bernstein and Dean Baker

One of most enduring, economically and socially damaging, downright frustrating facts about life in the United States is how expensive health care is here. Not only does U.S. health care cost far more than in other advanced economies, but compared with the nations that spend less, we have worse or equivalent health outcomes. In fact, U.S. life expectancy now lags behind that of all the advanced economies.

Add to those differences the latest outrage in health-care costs: surprise medical billing, when even well-insured patients can wake up from surgery finding that they owe thousands of dollars, because someone treating them while they were unconscious was out of their insurance network.

Chicago economics — only for Gods and Idiots

from Lars Syll

If I ask myself what I could legitimately assume a person to have rational expectations about, the technical answer would be, I think, about the realization of a stationary stochastic process, such as the outcome of the toss of a coin or anything that can be modeled as the outcome of a random process that is stationary. I don’t think that the economic implications of the outbreak of World war II were regarded by most people as the realization of a stationary stochastic process. In that case, the concept of rational expectations does not make any sense. Similarly, the major innovations cannot be thought of as the outcome of a random process. In that case the probability calculus does not apply.

‘Modern’ macroeconomic theories are as a rule founded on the assumption of rational expectations — where the world evolves in accordance with fully predetermined models where uncertainty has been reduced to stochastic risk describable by some probabilistic distribution. Read more…

Simpson’s Paradox

from Asad Zaman

Statistics and Econometrics today are done without any essential reference to causality – this is much like try to figure out how birds fly without taking into account their wings. Judea Pearl “The Book of Why” Chapter 2 tells the bizarre story of how the discipline of statistics inflicted causal blindness on itself, with far-reaching effects for all sciences that depend on data. These notes are planned as an accompaniment and detailed explanation of the Pearl, Glymour, & Jewell textbook on Causality: A Primer. The first steps to understand causality involve a detailed analysis of the Simpson’s Paradox. This has been done in the sequence of six posts, which are listed, linked, and summarized below

1-Simpson’s Paradox: Suppose that there are only two departments at Berkeley, and that they have different admit ratios for women. In Humanities 40% of female applicants are admitted, while in Engineering 80% are admitted. What will be the overall admit ratio of women to Berkeley? The overall admit ratio is a weighted average of 40% and 80% where the weights are the proportions of females who apply to the two departments. Similarly, if 20% of male applicants are admitted to Humanities while 60% are admitted to Engineering, then the overall admit ratio is a weighted average of 20% and 60%, with weights depending on the proportion of males which apply to the two departments. This is what lead to the possibility of Simpson’s Paradox. As the numbers have been set up, both Engineering and Humanities favor females, who have much higher admit ratios than male. If males apply mostly to Engineering, then the overall admit ratio for men will be closer to 60%. If females apply mostly to humanities, their overall admit ration will be closer to 40%. So, looking at the overall ratios, it will appear that admissions favor males, who have higher admit ratios. The key question is: which of these comparisons is correct? Does Berkeley discriminate against males, the story told be departmental admit ratios? Or does it discriminate against females, as the overall admit ratios indicate? The main lesson from the analysis in this sequence of posts is that the answer cannot be determined by the numbers. Either answer can be correct, depending on the hidden and unobservable causal structures of the real world which generate the data.

2-Simpson’s Paradox: This post elaborates on Read more…

Unrealistic mental models 6

from Asad Zaman

In the previous post (Three Types of Models 5), we discussed three types of models. The first type is based purely on patterns in observations, and does not attempt to go beyond what can be seen. This is an “observational” or Baconian model. The second type attempt to look through the surface and discover the hidden structures of reality which generate the observations we see. The best approach to this type of models has been developed by Roy Bhaskar, so we can call it a critical realist model or a Bhaskarian model. The third type of model creates depth and structures in our minds which create the patterns we see in the observations. The question whether our mental structures match reality is considered irrelevant. These may be called Kantian, or mental models. The models of modern Economics are largely Kantian, while Econometric models are largely Baconian. The key defect of both of these approaches is that they GIVE UP on the idea of finding the truth. Max Weber’s ideas about methodology played an important role in this abandonment of the search for truth, but it would take us too far away from our current concerns to discuss this in any detail. Briefly, Weber thought that heterogeneity of human motives made “explanation” of social realities via “truth” impossibly complex. Instead, he argued that we should settle for a weaker concept based on “ideal-types” – deliberately over-simplified models of behavior which create a match to observed aggregated patterns of outcomes. We now discuss the disastrous consequences of this abandonment of truth in greater detail.

There is a famous article of Milton Friedman on methodology in economic theory, which recommends the abandonment of truth: read more

Does it — really — take a model to beat a model?

from Lars Syll

A critique yours truly sometimes encounters is that as long as I cannot come up with some own alternative model to the failing mainstream models, I shouldn’t expect people to pay attention.

This is, however, to totally and utterly misunderstand the role of philosophy and methodology of economics!

As John Locke wrote in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding:

The Commonwealth of Learning is not at this time without Master-Builders, whose mighty Designs, in advancing the Sciences, will leave lasting Monuments to the Admiration of Posterity; But every one must not hope to be a Boyle, or a Sydenham; and in an Age that produces such Masters, as the Great-Huygenius, and the incomparable Mr. Newton, with some other of that Strain; ’tis Ambition enough to be employed as an Under-Labourer in clearing Ground a little, and removing some of the Rubbish, that lies in the way to Knowledge.

That’s what philosophy and methodology can contribute to economics — clearing obstacles to science by clarifying limits and consequences of choosing specific modelling strategies, assumptions, and ontologies. Read more…

In half a century what have we done with that knowledge?

from Edward Fullbrook

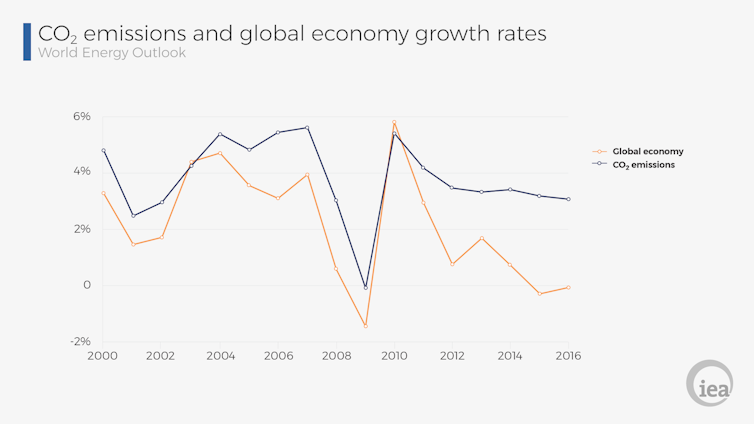

A version of this graph appeared in yesterday’s Guardian. I have a vivid memory from almost exactly half a century ago that relates to it. It was February 1970 and snowing. It was rural Wisconsin in the States and I was riding in a car with a woman who was the mother of six and a well-known peace activist but with no connection to science or environmentalism. We were coming from Frank Lloyd Wright’s estate Taliesin where I lived, and as we neared Madison and got caught in a traffic jam, my friend said, “That man in the car in front of us is one of the scientists who says we are increasing the Earth’s temperature.”

As the decades passed, my friend’s words became a milestone for me because they mark a point when the fact that the world’s economy was heating up the Earth had already become common everyday conversational knowledge. But now look again at that graph. What have we done with that knowledge?

What inequality?!

from David Ruccio

Economic inequality in the United States and around the world is now so obscene, and has convinced more and more people to do something about it, that the business press has initiated a campaign to deny its very existence.

They and the folks they represent are losing the battle of public opinion. And they’ve decided to do something about it.

First up was the Economist, the “newspaper” of record for liberal capitalism [ht: sk], claiming that new research undermines the pillars of the seemingly universal belief that “inequality has risen in the rich world.” Yes, as I have documented from the very beginning on this blog (e.g., here, here, and here), there are plenty of mainstream economists who have attempted to prove that inequality isn’t really a problem—either because it doesn’t really exist or, if it does, it’s not something we can or should do much about. And so the Economist managed to find pieces of research that call into question some of the key pillars of the inequality argument—that the gap between the top 1 percent and everyone else is growing, the middle-class is shrinking, capital is gaining at the expense of labor, and wealth inequality is soaring. Read more…

Where’s the Barefoot Revolution in economics?

from Blair Fix

Yesterday I was reminded of what got me interested in economics. I’ll preface this by saying that I make my living as a substitute teacher in Toronto. It’s not glamorous, but it pays the bills. It gives me time to do research from outside academia.

When I’m in high school classrooms, I always browse the posters on the wall. It’s funny what you see. You find things (both good and bad) that you’d never see in institutions of ‘higher learning’. It’s a daily source of amusement for me.

Yesterday, while browsing the posters on a classroom wall, I came across a copy of the ‘Barefoot Economics Manifesto’. I was delighted to rediscover this document, and surprised that it was sitting quietly in an otherwise normal classroom.

If you don’t know, the ‘Barefoot Economics Manifesto’ was a clarion call to reject neoclassical economics. I’m not sure when it was first published, but it seems to have come from Adbusters. (I can’t find the original document. If you know more about it, leave a comment.)

The manifesto goes by several names. Some call it the The True Cost Economics Manifesto. Others call it the Kick It Over Manifesto. Regardless of what you call it, here’s what the manifesto says: Read more…

Is economics — really — predictable?

from Lars Syll

As Oskar Morgenstern noted already back in his 1928 classic Wirtschaftsprognose: Eine Untersuchung ihrer Voraussetzungen und Möglichkeiten, economic predictions and forecasts amount to little more than intelligent guessing.

As Oskar Morgenstern noted already back in his 1928 classic Wirtschaftsprognose: Eine Untersuchung ihrer Voraussetzungen und Möglichkeiten, economic predictions and forecasts amount to little more than intelligent guessing.

Making forecasts and predictions obviously isn’t a trivial or costless activity, so why then go on with it?

The problems that economists encounter when trying to predict the future really underlines how important it is for social sciences to incorporate Keynes’s far-reaching and incisive analysis of induction and evidential weight in his seminal A Treatise on Probability (1921). Read more…

Recent Comments