Archive

Herman Daly has passed away

Herman Daly (1938-2022) was an early supporter of and a frequent contributor to the Real-World Economics Review, and the week before last, eleven days before he died age 84, he submitted an essay to RWER with this email.

Dear Edward,

I hope that you are well and surviving still in our disintegrating world. RWER continues as a voice of sanity. I am still kicking, but slowly, which has its benefits.

Attached is an article that I am submitting to RWER. Suggestions welcome.

All good wishes,

Herman

Herman’s essay “Ecological economics in four parables” will appear in RWER‘s next issue, early December.

https://www.worldeconomicsassociation.org/library/essays-against-growthism/

Can you think of something snappier than “Understanding the Economy – A Learning System”?

The 1300 words below are extracted from an email that Neva Goodwin wrote and copied me into. It outlines a large new project initiated by the World Economics Association, but which will include numerous other organizations opposed to the dominance of traditional economic thinking. However, the extract’s first sentence is misleading because it is Neva’s and Pratisha’s names that should be mentioned first since they are the project’s primary sources of creative energy. And then there is the question of the project’s name. As the project develops it will seek wide attention, and therefore needs a “snappier” name. Perhaps after reading Neva’s description, you can suggest one.

The project: “Understanding the Economy – A Learning System”

Edward Fullbrook, Pratistha Rajkarnikar, and Neva Goodwin have been working for several months to conceptualize a project designed to provide a good understanding of how economies work – and how they might work for greater human and planetary well-being – to people who are not economics students.

We start from acknowledging that humanity today is in an unprecedently dangerous situation which has been largely created by our economies. The situation has two prime dimensions. One, economies are redistributing wealth and income in a way that lethally threatens our socio-political systems. And two, human economies are impacting the biosphere and its ecosystems in a way that is rapidly destroying, maybe totally, the Earth’s capacity to sustain human life.

Given that the economies most responsible for this situation have been guided by the teachings of traditional economics, a fundamentally new discipline (and perhaps not to be called “economics”) must be quickly developed and made available to the public, especially to the young, who are increasingly aware of the crisis and have the most to lose.

The first stage of this project has included conversations with a variety of economists, including Jamie Galbraith, Andrew Mearman, Alicia Puyana Mutis, Bertrand Hamaide, John Komlos, Katherine N. Farrell, and Gar Alperovitz. Sam de Muijnck and Joris Tieleman, the leaders of Rethinking Economics/Our New Economy are involved with similar goals and activities to ours, and we hope to coordinate with them as well as with others similarly motivated, such as Leslie Harroun and Ted Howard at the Democracy Collaborative, to take advantage of our overlapping interests and activities. Our conversations to date have resulted in the following strategy statements:

Economics 999 and “the Monday night club problem”

from Edward Fullbrook

In 1965 in Berkeley, California the New Left came into existence by finding a solution to what its founders called “the Monday night club problem”, a problem remarkably similar to the one that decade after decade emasculates “heterodox economics”. In Berkeley there were numerous left-wing political groups, each based on a different set of underlying ideas, texts, and key terms, and that by long tradition met on Monday evenings. Each of these groups had its own informal hierarchy of members and its own way of describing and addressing political issues. Each group also provided valuable social support and intellectual enhancement for its members. But when it came to changing things, of having any real-word effect, they were no less powerless than bridge clubs.

It was not, however, that most Monday night club members did not want to bring about real-world changes; it was that they had no means of doing so. But in the fall of 1964 Read more…

Market-value in the news

from Edward Fullbrook

Over the weekend I read two articles (1, 2) in The Guardian about market-value. One concerned the painter Bansky, the other a truffle hunter in Croatia.

I’ve been fan of Bansky for twenty years, beginning when he was a local graffiti artist in my part of town. A couple of years ago one of his paintings, Girl With Balloon, was auctioned at Sotheby’s in London for £1.1m.

As soon as the auctioneer’s hammer fell, Bansky’s canvass “passed through a secret shredder hidden in its large Victorian-style frame, leaving the bottom half in tatters and only a solitary red balloon left on a white background in the frame.” Here is the one-minute video. Read more…

Steve Keen vs. Nordhaus – regarding humankind’s greatest ever crisis

from Edward Fullbrook

Steve Keen’s new paper “The appallingly bad neoclassical economics of climate change,” would benefit humankind if it were widely read by economists.¹ There are two ways you can obtain it:

Here is its conclusion:

Conclusion: drastically underestimating economic damages from global warming

Were climate change an effectively trivial area of public policy, then the appallingly bad work done by Neoclassical economists on climate change would not matter greatly. It could be treated, like the intentional Sokal hoax (Sokal, 2008), as merely a salutary tale about the foibles of the Academy.

But the impact of climate change upon the economy, human society, and the viability of the Earth’s biosphere in general, are matters of the greatest importance. That work this bad has been done, and been taken seriously, is therefore not merely an intellectual travesty like the Sokal hoax. If climate change does lead to the catastrophic outcomes that some scientists now openly contemplate (Kulp & Strauss, 2019; Lenton et al., 2019; Lynas, 2020; Moses, 2020; Raymond et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2020; Yumashev et al., 2019), then these Neoclassical economists will be complicit in causing the greatest crisis, not merely in the history of capitalism, but potentially in the history of life on Earth.

1. More than once Keen distances his usage of “climate change” from greenwash usage, as when he writes: “these Neoclassical economists are on a par with United States President, Donald Trump, in their appreciation of what climate change entails. . . . . They are equating the climate to the weather.”

The Inequality Crisis: The three options

Amazon US UK DE FR ES IT JP CA

The everyday operations of our economies produce the goods and services that keep us alive and enable us to enjoy life. But that is not the only way that those operations effect our lives; they also effect societies and ecosystems. The Inequality Crisis, which threatens our societies, and the Climate Crisis, which threatens both our societies and our species, are also, no less than production, brought about directly by the everyday operations of our economies.

But for two hundred years the economics profession has in the main excluded from its study of economies two of their three categories of primary effects. And given the profession’s influence, this exclusion of societal and ecological effects has promoted the intellectual invisibility of these two categories, thereby helping to bring about the two crises. Read more…

Isolation Waltz

from The Guardian

Move over Mozart, here comes Stelios Kerasidis. A seven-year-old Greek prodigy has penned an “isolation waltz” inspired by the pandemic.

The hypnotic, fugue-like melody has picked up more than 43,000 hits on YouTube since its launch last week.

“Hi guys! I’m Stelios. Let’s be just a teeny bit more patient and we will soon be out swimming in the sea,” he beams, perched on his piano stool, feet barely touching the floor. “I’m dedicating to you a piece of my own.”

The work, his third composition, was written especially “for people who suffer and those who isolate because of Covid-19,” he adds.

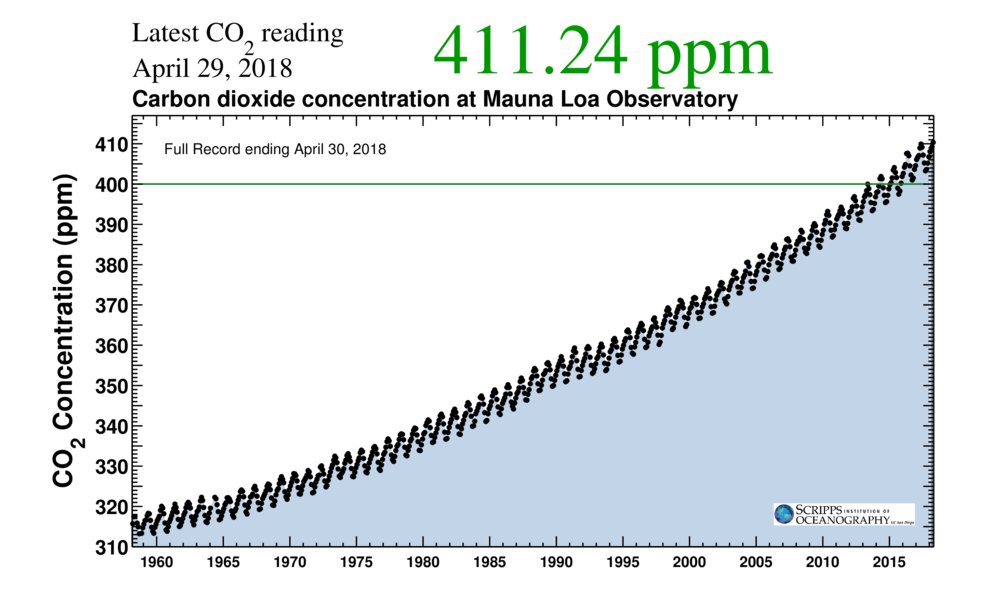

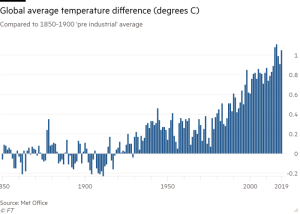

In half a century what have we done with that knowledge?

from Edward Fullbrook

A version of this graph appeared in yesterday’s Guardian. I have a vivid memory from almost exactly half a century ago that relates to it. It was February 1970 and snowing. It was rural Wisconsin in the States and I was riding in a car with a woman who was the mother of six and a well-known peace activist but with no connection to science or environmentalism. We were coming from Frank Lloyd Wright’s estate Taliesin where I lived, and as we neared Madison and got caught in a traffic jam, my friend said, “That man in the car in front of us is one of the scientists who says we are increasing the Earth’s temperature.”

As the decades passed, my friend’s words became a milestone for me because they mark a point when the fact that the world’s economy was heating up the Earth had already become common everyday conversational knowledge. But now look again at that graph. What have we done with that knowledge?

2019 was “one of the strongest in the history of financial markets.” What does that mean?

from Edward Fullbrook

Here is a passage from an article that appeared last week in The Guardian.

With one day of trading to go, 2019 is on course to be one of the strongest in the history of financial markets after shares around the world racked up record after record in another barnstorming year.

On Wall Street the Dow Jones industrial average has gone up almost 25% having reached record highs day after day, while the broader S&P500 is up 30% and the tech-heavy Nasdaq has grown 40% in value. The FTSE100 in London is close to its record high, as is the Dax30 in Germany. In the Asia Pacific, the Nikkei is up 15% while Australia’s ASX200 is still close to its highest ever point (reached in November).

But none of these countries, with the exception of the US, are in particularly good shape. Instead their stock markets are being sustained by ultra-low borrowing costs led by the US Federal Reserve.

This latest round of rate cutting has turned many of the assumptions about economics on their head to create a bad-news-is-good-news paradigm for markets.

Do these huge increases in the market-values of stocks mean that the riches of the world, including assets and income, have increased hugely in 2019? That depends on what kind of metrical structure market-value has. Read more…

“The economics profession is facing a mounting crisis of sexual harassment, discrimination and bullying”

from yesterday’s New York Times

The economics profession is facing a mounting crisis of sexual harassment, discrimination and bullying that women in the field say has pushed many of them to the sidelines — or out of the field entirely.

Those issues took center stage at the American Economic Association’s annual meeting, the largest gathering of the profession, last weekend in Atlanta. Spurred by substantiated allegations of harassment against one of the most prominent young economists in the country, top women in the field shared stories of their own struggles with discrimination. Graduate students and junior professors demanded immediate steps by the A.E.A. to help victims of harassment and discipline economists who violate the group’s newly adopted code of conduct.

The Great Gatsby Curve

from The Atlantic

Economists represent this concept with a number they call “intergenerational earnings elasticity,” or IGE, which measures how much of a child’s deviation from average income can be accounted for by the parents’ income. An IGE of zero means that there’s no relationship at all between parents’ income and that of their offspring. An IGE of one says that the destiny of a child is to end up right where she came into the world.

Economies, carbon dioxide and the atmosphere

In April the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere exceeded an average of 410 parts per million (ppm). Before the Industrial Revolution, carbon dioxide levels did not exceed 300ppm in the last 800,000 years. (Scripps Institution of Oceanography)

Citigroup Plutonomy Reports update

from Edward Fullbrook

“Plutonomy” is the word that Wall Street and City bankers use in private to designate the political economy in which they operate and in which today we all live. They go to great trouble to keep us 99% ignorant of their perceptions of today’s economic and political realities, and which their “plutonomy” concept reveals.

In November 2010, I put up the post Citigroup attempts to disappear its Plutonomy Report #2 which was viewed over 40,000 times. It included links to Citigroup’s Plutonomy Reports 1 and 2, but Citigroup soon succeeded in having those links blocked.

In January 2011 I put up the post New links for secret Citigroup Plutonomy Reports. But in June 2011, Citigroup succeeded in also closing down those links. Here is an account of how they did it, including some excerpts from the reports.

But recently someone sent me this link:

http://combatblog.net/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Citigroup-Plutonomy-Report-Part-2.pdf

It is not exactly a good read, but nonetheless very interesting. It estimates that already in 2006 in the US the richest 5% possessed greater net worth than the bottom 95% combined.

I was also sent this:

After a little digging, I was able to find .jpeg images of all the pages of Parts 1 and 2 of the report. While they are not high-quality images, they are legible enough to download and read.

As of today (4/23/18), the images can be found at this link:

https://our99angrypercent.wordpress.com/

I am told that there also exists Plutonomy Report #3, but I have yet to access it

Syll’s top 20 books compared to RWER’s top 10 and its poll’s top 40 vote receivers

In May of 2016 the Real-World Economics Review conducted a poll titled “Top 10 Economics Books of the Last 100 Years” Voting was open to the journal’s 26,000 subscribers, and over 3,000 of them voted, each having up to ten votes and with 17,270 votes in total cast. The results were published two weeks later and linked on over 2,000 Facebook pages. It is interesting to compare those results to Lars Syll’s personal list of “Top 20 heterodox economics books” published here earlier today.

Although the RWER subscribers list was not limited to “heterodox” economics books, eight of Syll’s top 20 appear in the RWER subscribers’ Top Ten.

Pasted below are the 40 books in the RWER poll that received the most votes. Notably, Syll’s list contains only one book published in this millennium and the RWER’s top 20 only three.

The 40 books that received the most votes in the RWER poll for the

Top 10 Economics Books of the Last 100 Years

- John Maynard Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936) 1,597

- Karl Polanyi, The great transformation (1944) 1,027

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, Capitalism, Socialism & Democracy (1942) 927

- John Kenneth Galbraith, The Affluent Society (1958) 780

- Hyman Minsky, Stabilizing an Unstable Economy (1986) 731

- Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2014) 687

- Joan Robinson, The Accumulation of Capital (1956) 583

- Michal Kalecki, Selected Essays on the Dynamics of the Capitalist Economy (1971) 582

- Amartya Sen, Collective Choice and Social Welfare (1970) 580

- Piero Sraffa, Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities (1960) 500

Bribe offers for academics

from Edward Fullbrook

Norbert Häring’s story about misleading academic research reminds me of another story.

Big-money offering bribes to academics is, I suspect, more common than people, including academics, realize. I first encountered the practice when I was an undergraduate. My university’s most popular course, “Insurance”, was taught by an economics professor whose students affectionately called Doc Elliot. He taught not only how the insurance industry purported to work, but also how it really worked, and he frequently accepted off-campus speaking engagements.

Doc Elliot may be the only person who has ever lived who could talk insurance and make people laugh. Certainly, he was the funniest person I’d ever known; and, despite our 35-year age gap, we became friends of a sort. One day I was sitting with him in his office when, handing me a business letter, he said, “Here, this is what a bribe offer looks like.”

The letter was from a national association of insurance companies. It praised his eminence as a world authority on insurance and said they would like to be able to occasionally call on him for advice. For this they would pay him $80,000 a year. At the time the university’s highest professor’s salary was $10,000, and so far as I know there was no money in this professor’s family.

“In the world we live in,” explained Doc Elliot, “refraining from telling the truth is often worth lots more than telling it. I get between-the-lines offers like this all the time. But I think this one deserves to go up on my bulletin board.”

Why does it cost so much to read heterodox economics?

from Edward Fullbrook

The current issue (January 8, 2018) of the Heterodox Economics Newsletter lists the current issues of 16 English language journals, with each linked to the newsletter’s website where there is a link for each article in these new issues. For each journal, I picked one article to try to read. Here is what I found. Read more…

Neoclassical economics usually reads its models backwards.

from Edward Fullbrook

In public, including in the training of economists, Neoclassical economics usually reads its models backwards. This gives the illusion that they show the behaviour of individual economic units determining sets of equilibrium values for markets and for whole economies. It hides the fact that these models have been constructed not by investigating the behaviour of individual agents, but rather by analysing the requirements of achieving a certain macro state, that is, a market or general equilibrium. It is the behaviour found to be logically consistent with these hypothetical macro states that is prescribed for the individual agents, rather than the other way around.[1] This macro-led analysis, this derivation of the micro from a macro assumption, is and always has been the standard analytical procedure of theory construction for the Neoclassical narrative. Sometimes, for pedagogical reasons, authors call attention to how the “individualist” rabbit really gets into the Neoclassical hat. For example, consider the following passage from a once widely used introduction to economics.

“For the purpose of our theory, we want the preference ranking to have certain properties, which give it a particular, useful structure. We build these properties up by making a number of assumptions, first about the preference-indifference relation itself, and then about some aspects of the preference ranking to which it gives rise” (emphasis added) (Gravell and Rees 1981, p. 56).

This intellectual cult threatening us all

from Edward Fullbrook

Determinism, the idea that everything that happens must happen as it does and could not have happened any other way, and atomism, the idea that the world is made up of entities whose qualities are independent of their relations with other entities, are fundament components of classical mechanics. Atomism is also central to the concept of mind developed in John Locke’s An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, published (1690) three years after Newton’s Principia. Locke’s general conception of the human mind became commonplace among 18th-century philosophers, so when Adam Smith came to write the foundational text for economics, The Wealth of Nations (1776), he had the example not only of Newton’s material atomism, but also of Locke’s extension of it to an altogether different area of inquiry. If atomism could form the basis of a theory of ideas, then why not apply it as well to a theory of human beings?

Of course Smith did not limit his vision of economic reality to what could be seen through the metaphysical lens of classical mechanics. But a century later the founders of Neoclassical economics did exactly that and even boasted that they were doing so. Their justification of course – and it was a plausible one at the time – was the enormous success that exclusive devotion to this approach had yielded in physics. In time, especially from the 1960s onwards, undivided allegiance to this determinist-atomistic narrative became, with few exceptions, a basic requirement for making a career in economics. Read more…

Recent Comments