The big picture. Economic history links-of-the-day

The reconstruction of (macro-)economics is on its way. And we seem to be in the ‘big stories’ phase. On this blog, Peter Radford had a ‘it’s political economy after all’ story: ‘Austerity: democracy versus capitalism’ while David Ruccio wrote about his surprise that ‘History and capitalism‘ suddenly had become a fad. But they were not the only ones to take a broad view – quite some big boys weighed in, too: (I) Brad deLong, (II) Tyler Cowen, (III) George Soros and (IV) William Janeway. Below some extensive quotes and a few remarks

Ad I. Brad de Long is the economic historian and tells the story of the unprecedented increase in prosperity during the last 250 years. What I would like to add (based upon my scientific work, by the way, not just as a commenter – I claim some authority here) is that Brad neglects

(a) the subsequent waves of ever-increasing urbanization in Flanders (fifteenth century), Holland (sixteenth/seventeenth century), the United Kingdom (eighteenth/nineteenth century) and subsequently the rest of Europe and the rest of the world, a process which is of course still going on.

(b) the in the long run increasing quality and value of houses as well as the ever- increasing numbers and value of ‘utensils’ in these houses, a process which started at the latest in the sixteenth century. Around 1540, it was entirely possible that the bed (good wood, blankets, cushions – a consumer durable) was more expensive than the house around it (loam, reed, rotten wood – basically a kind of ‘disposable’). Really. In 1640 this was at least in the Netherlands an exception. This aspect of ‘modern economic growth’ does not always receive the attention it deserves.

(c) the decline of the ‘biological standard of living’ in the nineteenth century: people became shorter and less healthy and for the Netherlands I can only agree with Robert Fogel that (in the Netherlands, too) it was only after 1895 that standards of living surpassed maximum pre-industrial standards, despite 75 years of increase of per capita GDP and technological progress.

Lets give the floor to DeLong:

If you are telling a story of the history of five hundred years ago, you most-likely focus on Martin Luther and Jean Calvin’s Protestant Reformation, on the Spanish conquest of the Americas, on the rise of the Shāhān-e Gūrkānī—the Moghul Empire—in the Indian subcontinent, and maybe a couple more. Those are the axes of the history of the 1500s: religion, expansion, and conquest. If you are telling a story of a thousand years ago, you most-likely focus on the rise of the Song Dynasty in China, on the waning of the golden age that was Abbasid Baghdad-centered Islamic civilization, and on, perhaps, the establishment of feudal “civilization” in western Europe. Those are the axes of the history of the 1000s: politics and culture. Other stories of other centuries would most-likely focus on the Christianization of the Roman Empire, the shift of China’s population center of gravity to the rice-growing south and so forth. The rise, diffusion, and fall of dynasties, empires, religions, and cultures are the axes of history, with perhaps some reference to what the cultures of material subsistence in the background were and how they slowly changed.

But what will people 500 years in the future see the principal axes of our history, of the history that set the patterns into which their civilization grew, of the history of the extended 1870-2010 twentieth century?

The major theme has to be that the history of the twentieth century was overwhelmingly economic and was—all in all—glorious. The history has an extremely depressing middle: a wolf-fanged century, wrote Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, “but I am not a wolf”. However unlikely it seemed in his time, our ending today is—so far—much more happy than tragic. Certainly this is the case when we use a relative yardstick, and compare the end of the twentieth century to all previous centuries. Yes, forms of religious strife and terror that we thought we had left behind several centuries ago are back. Yes, failures of economic policy that land countries in depression that we thought we had learned how to resolve decades ago are back. Yes, nuclear weapons and global warming pose dangers for the future of a magnitude that humanity has never before confronted. Nevertheless, all in all the North Atlantic today is a (relatively) free and prosperous region, and the rest of the world is if not free and prosperous at least closer to being so than at any time in the past.

Ad II. Tyler Cowen has ‘Another way of thinking about the European economic collapse‘.

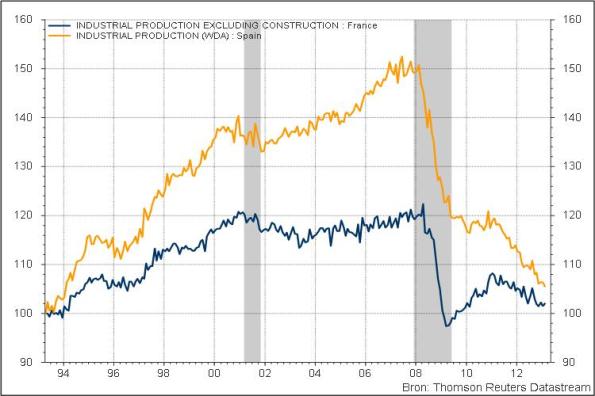

It’s basically the competitivity story. To an extent I agree. The 2,5 million jobs lost in the Spanish construction sector and related industries are not coming back, ever (well, maybe 250.000 of them, in five years time). And I completely agree with Tyler’s implicit argument that it’s not ‘creative destruction’ but ‘destructive creativity’ which drives capitalist growth. Cars were not invented after we removed horses from the cities – cars came and destroyed the traditional transport sector’. You do not need to destroy the old to make room for a new sector – a new sector will destroy the old one and carve out its own space. Stronger: the demise of about the most important sector of the economy (i.e. building and related industries in Spain) will not necessarily lead to the growth of new sectors, not in the short run but also not in the medium (5-8 years) of even long run (twenty years). And low aggregate demand will only contribute to the European Economic Blues, as Tyler contends (he dislikes fiscal policy but wants nominal GDP to grow faster, which is another way of stating that he wants lower interest rates and more ‘Keynesian’ aggregate spending, as long as it isn’t devious government spending). Tyler doesn’t however stress the huuuuuge capital flows and epic building booms and busts and large and unsustainable intra-European current account imbalances before 2008 but stresses ‘China’ (and implicitly of course other ‘low wage/but unlike the days of yonder high technology’ competitors). The recent ECB working paper 1531 explores the devastating consequences of these capital flows for the competitivity of the Irish economy. Live would have been better without them. But Tyler has a point. There are a lot of caveats to the next graph but sometimes you caveats are not important:

Tyler is also right to (implicitly) define ‘flexibility’ as including technological prowess and the ability to produce new stuff instead of giving more power to mediocre managers. But the ridiculous idea that income inequality is caused by textbook market forces… If those worked, CEO’s of banks would earn 50.000,– instead of 500.000,– and more a year and interest on my savings account would be higher. I mean – banking is not exactly rocket science, a hundred years ago it often was an ‘evening job’ for the local schoolteacher, or another member of the countryside elite. Also, I still do not believe that in the medium run the UK labor market (which added jobs because/while productivity declined with a historical 2,4% per hour) defies Okun ‘s rule of thumb, i.e. the UK will need more economic growth to increase employment (Italian unemployment was of course relatively low without economic growth for decades – but that only holds when you look at U-3 unemployment. U-6 unemployment in Italy is skyhigh, too). Tyler:

Let’s start with a few claims that (most) people agree with:

1. U.S. median income is down since the 1990s and down almost eight percent since the end of the recession in 2009.

2. The U.S. has higher income inequality than most of Europe and our high earners have done quite well for some time.

3. Many events happen in the U.S. first.

4. The U.S. is more flexible than most European economies, though not obviously more flexible than say Germany or Sweden.

OK, let’s tie those pieces together, but please keep in mind that I consider the following to be speculative.

IT and China, taken together, seem to imply a big whack to median income. This whack should be higher for the less flexible polities, and furthermore the wealthy and the well-educated in the U.S. get back a big chunk of that money through tech innovation and IP rights. Plus we’ve had some good luck with fossil fuels and even the composition of our agriculture. If you had a country without those high earners in the tech sector, and an inflexible labor market, those economies will have to contract and I don’t just mean in a short-term cycle. Equilibrium implies negative growth for those economies, at least for a while.

By how much? If the relatively flexible U.S. lost 8% of median income, perhaps Italy and Spain and Greece have to lose 15%, but with no offsetting major gains on the upper end of the income distribution. (How flexible is Ireland or for that matter France is an interesting question and so far the answer is not obvious.) In sum, the less flexible European economies will lose at least 15% of their gdps, due to trade and technology. There is then the question of what the path downwards will look like and feel like. Being in the eurozone makes adjustment much harder, and brings the doom more quickly, for reasons which are by now well-discussed.

George Soros: ‘Dear and beloved German brethren and sistern. Please, please end this stupid, inconsistent, ill-conceived and retarded monetary sadism. You increased interest rates for countries with severe economic crises, which aggravated the crises which and was bad for everybody and for you too. People who do not work can’t pay back their debts and do not innovate. You-will-have-to-decrease-these-rates’. If you don’t – leave the Euro. Soros:

My objective in coming here today is to discuss the euro crisis. I think you will all agree that the crisis is far from resolved. It has already caused tremendous damage both financially and politically and taken an extensive human toll as well. It has transformed the European Union into something radically different from what was originally intended. The European Union was meant to be a voluntary association of equal states but the crisis has turned it into a creditor/debtor relationship from which there is no easy escape. The creditors stand to lose large sums of money should a member state exit the union, yet debtors are subjected to policies that deepen their depression, aggravate their debt burden and perpetuate their subordinate status.

Germany is in the driver’s seat and that is what brings me here.

What caused the crisis? …. In my view it cannot be properly understood without realizing the crucial role that mistakes and misconceptions have played in creating it. The crisis is almost entirely self-inflicted. It has the quality of a nightmare … But the euro had many other defects, which went unrecognized. For instance, the Maastricht Treaty took it for granted that only the public sector could produce chronic deficits because the private sector would always correct its own excesses. The financial crisis of 2007-8 proved that wrong. The fatal defect was that by creating an independent central bank, member countries became indebted in a currency they did not control. This exposed them to the risk of default.

Developed countries outside a currency union have no reason to default; they can always print money. Their currency may depreciate in value, but the risk of default doesn’t arise. By contrast, third world countries that have to borrow in a foreign currency like the dollar run the risk of default. To make matters worse, such countries are exposed to bear raids. In short, the euro relegated what is now called the periphery to the status of third world countries.

Chancellor Merkel read public opinion correctly when she declared that each country should look after its own financial institutions individually instead of the European Union doing it collectively. In retrospect that was the first step in a process of disintegration.

It took financial markets more than a year to realize the implications of Chancellor Merkel’s declaration, demonstrating that they too operate with far-from-perfect knowledge. Only at the end of 2009, when the extent of the Greek deficit was revealed, did the markets realize that a Eurozone country could actually default. But then they raised risk premiums on all the weaker countries with a vengeance. This rendered commercial banks, whose balance sheets were loaded with those bonds, potentially insolvent and that created both a sovereign debt and a banking crisis – the two are linked together like Siamese twins.

There is a close parallel between the euro crisis and the international banking crisis of 1982. Then the IMF and the international banking authorities saved the international banking system by lending just enough money to the heavily indebted countries to enable them to avoid default but at the cost of pushing them into a lasting depression. Latin America suffered a lost decade.

Today Germany is playing the same role as the IMF did then. The setting differs, but the effect is the same. The creditors are in effect shifting the whole burden of adjustment on to the debtor countries. Please note how the terms “center” and “periphery” have crept into usage almost unnoticed, although in political terms it is obviously inappropriate to describe Italy and Spain as the periphery of the European Union.

William ‘I love Schumpeter’ Janeway (and I believe that Asia will become a ‘frontier’ economy, especially in life sciences and bionics (already the wave of the future):

HONG KONG – For 250 years, technological innovation has driven economic development. But the economics of innovation are very different for those at the frontier versus those who are followers striving to catch up.

At the frontier, the innovation economy begins with discovery and culminates in speculation. From scientific research to identification of commercial applications of new technologies, progress has been achieved through trial and error. The strategic technologies that have repeatedly transformed the market economy – from railroads to the Internet – required the construction of networks whose value in use could not be known when they were first deployed.

Consequently, innovation at the frontier depends on funding sources that are decoupled from concern for economic value; thus, it cannot be reduced to the optimal allocation of resources. The conventional production function of neoclassical economics offers a dangerously misleading lens through which to interpret the processes of frontier innovation.

Financial speculation has been, and remains, one required source of funding. Financial bubbles emerge wherever liquid asset markets exist. Indeed, the objects of such speculation astound the imagination: tulip bulbs, gold and silver mines, real estate, the debt of new nations, corporate securities.

Occasionally, the object of speculation has been one of those fundamental technologies – canals, railroads, electrification, radio, automobiles, microelectronics, computing, the Internet – for which financial speculators have mobilized capital on a scale far beyond what “rational” investors would provide. From the wreckage that has inevitably followed, a succession of new economies has emerged.

Complementing the role of speculation, activist states have played several roles in encouraging innovation. They have been most effective when pursuing politically legitimate missions that transcend narrow economic calculation: social development, national security, conquering disease.

In the United States, the government constructed transformational networks (the interstate highway system), massively subsidized their construction (the transcontinental railroads), or played the foundational role in their design and early development (the Internet). Activist states around the world have funded basic science and served as early customers for the novel products that result. For a quarter-century starting in 1950, the US Department of Defense – to cite one crucial example – combined both roles to build the underpinnings of today’s digital economy.

For countries following an innovative leader, the path is clear. Mercantilist policies of protection and subsidy have been effective instruments of an economically active state. In the US, the first profitable textile mills blatantly violated British patents. And ferociously entrepreneurial private enterprise was supported by a broad array of state investments, guarantees, and protective tariffs, in accordance with the “American System” inspired by Alexander Hamilton and realized by Henry Clay.

The great, neglected German economist Friedrich List, a student of Hamilton’s work, laid out an innovation roadmap for his own country in 1841, in his National System of Political Economy. It has been used repeatedly: by Japan beginning in the last decades of the nineteenth century; by the Asian Tigers in the second half of the twentieth century; and now by China.

List noted how Britain’s emergence as “the first industrial nation” at the end of the eighteenth century depended on prior state policies to promote British industry. “Had the English left everything to itself,” he wrote, “the Belgians would be still manufacturing cloth for the English, [and] England would still have been the sheepyard for the [Hanseatic League].”

Coherent programs to promote economic catch-up are relatively straightforward. But the transition from follower to leader at the frontier of the innovation economy is more challenging and elusive.

The US managed the transition roughly between 1880 and 1930, combining the professionalization of management with a speculative taste for new technologies – electrification, automobiles, and radio – and state tolerance of the Second Industrial Revolution’s great industrial monopolies, which invested their super-profits in scientific research. The post-World War II invocation of national security as the legitimizing rationale for an economically active state extended America’s leadership.

It is not yet clear whether East Asia’s economic powerhouses will succeed in making the transition from follower to frontier.

Additional literature:

Knibbe, M., (2010) ‘Regionale verschillen in urbanisatiedynamiek, Nederland 1796-1950’ in; Collenteur, G., M. Duijnvendak en R. Paping and De Vries, H. (eds.), ‘Stad en Regio’ pp. 323-332.

Recent Comments